For the most part the meters we have work adequately, however, we need to know how to interpret what they do and do not tell us.

In today’s world of digital we have become obsessed with peak levels and the 0 dBFS point on our digital equipment. This is understandable because going beyond this level has dramatic consequences, while being almost anywhere below it has relatively subtle consequences.

We do try to always push our levels right up to that limit. (A full diatribe on all the misunderstandings about levels in digital systems is beyond the scope of this writing, but suffice to say many of the “common sense” practices in use today are somewhat misguided.)

Regardless of the valid and invalid reasons for this, the result is that many engineers stay primarily focused on that peak level and don’t really think a whole lot about what is going on below that.

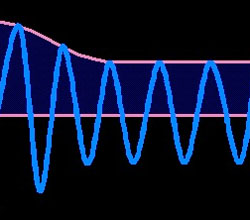

In the mastering world one of the prevailing trends has been to remove so much dynamic range from material that the average level is extraordinarily loud.

Everyone wants their song or CD to sound as loud or louder than the other material out there so mastering engineers are forced to push the envelope, which often results in most of the dynamic range being squashed out of the material.

A small part of the problem here is that the meters mostly used do not accurately show how high the overall energy level is getting, as explained in yesterday’s tip. Engineers don’t “see” what they are doing to the audio. Clearly the judgment should come down to what it sounds like anyway.

Ultimately this is among the aesthetic decisions that can be made for a given recording. So long as the material doesn’t go above 0 dBFS it’s a “legal” recording.

Anything beyond that is largely a matter of taste, so it’s not as if inaccurate metering is a real show stopper, but many engineers actually rely on meters more than they’d probably like to admit.

This is illustrated effectively in how their eyes are glued to those “over” indicators on their DAW or digital recorder.

As mentioned before, various meters react to this phenomenon differently. Peak meters will not show any difference because they, by definition, aren’t concerned with average levels.

VU style meters give some indication if you know what to look for. LED meters, which often are some attempt at a compromise between peak and average meters, will give similar clues.

Assuming you don’t have the disposable income to invest in the sophisticated metering systems many professional mastering engineers use, you can learn to better use what you already have.

Put in four or five different CDs of different styles of music you like and notice how the meters you normally use to set your levels react to them. Don’t just look at the top line. Look at how far down they go, and how quickly they seem to be moving.

This gives you some idea of how they are reacting to the dynamics of the music. You can use this knowledge as you watch the meters when your material is playing.

Keep in mind that in many cases these recordings were produced on state-of-the-art equipment by some of the best people in the business. Don’t expect to be able to duplicate what they do exactly.

Further, there’s almost surely a lot your meters don’t/can’t tell you. So just because you can make them look the same on your material as compared to another CD doesn’t necessarily mean it Is the same.

For more tech tips go to Sweetwater.com