Stage Details

A recent trip to the Mucky Duck was to support a performance by Max Stalling, a native Texan with a unique musical style that rolls from two-stepping dance numbers to Spanish-guitar-heavy folk music (à la Marty Robbins), with a few waltzes mixed in.

Max sings and plays the acoustic guitar, and is backed by a three-piece rhythm section comprised of Jason Steinsultz on upright bass, Jeff Howe on drums, and Bryce Clark on lead guitar, switching between mandolin, steel string and gut string acoustics, and electric guitar.

Both Jason and Bryce sing harmony, and steel guitar player Hank Early also sat in for this show, I used the band’s own Shure Beta 58s microphones for vocals, a house-supplied AKG D112 on kick, and Shure SM57s on electric guitar and steel. The upright bass and three acoustics all had band-supplied Radial Tonebone preamps and ran direct.

Just one of my AKG 451e condensers was used for drum overhead, to capture the kit as a whole. Jeff (the drummer) switches between sticks, brushes and even sometimes wrapped mallets. I will heavily compress the overhead (remember, the acoustic drum sound is still dominant in the room) so that the details on the brushes and mallets are not lost. Having at least one drum mic also lets me add reverb to this very dry room.

Max is very particular about his monitor mix. Some engineers take this as being a “prima donna” but I’ve found it to be exactly the opposite. He knows what he wants and isn’t afraid to ask. He can’t state specific frequencies, so there’s a bit of interpretation needed to get his mix the way he wants it, but once he’s comfortable, that’s pretty much that.

The tone that Max wants out from his monitor is not exactly what you want at front of house. He likes things a little dark with plenty of low mids for both his vocal and guitar. Two of the XLR wyes allowed me to split his vocal and acoustic channels so that I was able to give him exactly the tone he wanted in the monitor by using the channel strip EQ. Then I had use of the 15-band graphic for his mix to tame the little bit of feedback that tried to creep in.

Starting Quiet

After getting the monitors set, I build the front of house mix. The best way to mix in this room is to listen to what’s coming off the stage and only add what’s needed. Trying to overpower the stage volume is a losing battle.

I always start my sound check with the house PA off and just listen to what’s happening on stage, and then work to fill in the missing bits that will help make the performance “pop.” I’ve noted several times that it seems like I’m cutting too much low-mid out of the house, but that’s usually O.K. because the monitors provide all of the low-mid energy one could ever want.

I get the vocals up to a good level, over the stage volume, and only after do I work in the other instruments. Generally, the drums and amplified instruments are fine coming straight off the stage. On the recent gig with Max, I needed a touch of the electric guitar and steel, but none of the bass and kick drum.

Jeff plays a kit of Slingerland Radio Kings from the 1940s. These drums are big and loud. The kick is a huge 14 inches by 26 inches and uses a ported head. (Back in the “good old days” the drums had to fend for themselves, and this set gives you all the stage volume you need!)

But here, because we’re already plenty loud in the house, I used the overhead high-passed around 100 Hz and compressed at a 6 to 1 ratio with about 12 to 15 dB of reduction on the loud parts to add definition and to help keep the mix cohesive all the way to the back of the room. It was also used to feed the reverb.

Same Room

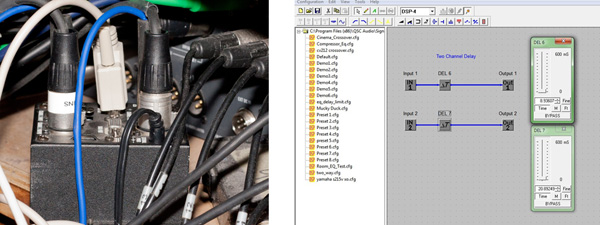

The house console is a 24-channel Allen & Heath GL2400, a step above what you find in many clubs the size of the Mucky Duck. Most bands will not fully mic the drums, so 24 channels gives me plenty of room to split channels as needed.

I maximize the two available channels of compression on the venue’s dbx 1066 by inserting each on a bus and assigning several like channels to that bus. I used one compressed bus for the drums and another for the lead acoustic and a gut string acoustic that are featured prominently in the band.

There are also two Lexicon effects units – MPX110 and MX400 – on hand to add ambiance. To create a sense of space in this dry, tightly packed room, I used a trick that I’ve implemented in most of my live mixes for the past couple of years. I select a very short and transparent “room” style reverb and send the entire band to it, typically applying about a half second of decay and zero pre-delay.

Then, I bring it up in the house until it can be heard clearly, then back it down to just on the edge of being noticed. If the reverb is muted, a change can be heard, but it’s not something you can pinpoint. I find that this really takes a tight mix and glues it together even more – the band is all playing in the same “room” together because they all have the same decay time.

If you’re lucky enough to have a gig in the Mucky Duck, be prepared to bring your A game. It’s a bit challenging, but once the mix is dialed in you can be sure you’re mixing for a crowd that truly appreciates what you’re doing.

Editor’s note: This article originally appeared on PSW in 2014.