Generator & Distro Power

If you’re working on a large stage with dedicated power or an outside venue fed by a generator, you’ll often bring along your own electrical distribution system know as the “power distro.”

And many times that power distro system will be fed by large twist-lock connectors generically know as cam locks. These are big brass connectors the size of a banana with rubberized insulating covers that keep you from getting shocked while touching the exterior.

They come in colors corresponding to their connection type, so a green cam lock is ground, white is neutral, and black, red, or blue are hot (at least in America). Sometimes the cam lock covers will all be black with a wrap of white, green, blue or red electrical-tape in the middle to define their usage and that’s legal as well.

Here (below right) is what a portable distro panel looks like with the green, white, black and red cam lock inputs across the bottom.

Cam locks are typically fed by a single, double or triple 100- to 200-amp circuit breaker at the generator or house panel, so you’ll need to provide your own 20-amp breakers downstream to feed your portable backline power outlets in order to prevent the wires from melting in the event of an overload.

You can see the circuit breakers across the top of the panel at the left. Also, you’ll occasionally find a 3-phase house system with green, white, red, black and blue cam locks which will meter as 120/208 volts, but we’ll discuss that topic towards the end of this series.

Also note the difference between the 20-amp and 15-amp versions of the stage outlets as shown a few illustrations back. A 20-amp outlet will have another sideways slot for the neutral connection, while a 15-amp outlet will only have a single vertical slot.

The Measurements

Since we’re going to be measuring live voltage, observe the safety rules from part I of this series:

• Use only one hand to hold the plastic handles of the meter leads, put your other hand in your back pocket so you don’t lean it on anything conductive

• Be sure you don’t touch the metal tip portion of either meter lead

• Don’t stand or kneel on wet ground while testing voltages. For most situations, dry sneakers will insulate you from the earth sufficiently, and if you’re doing this test on a dry stage then the wooden floor or carpet will protect you if something goes wrong.

But if you’re going to measure voltage at a waterlogged festival generator I suggest standing on a dry rubber shower mat or dry plywood so your feet are insulated from the ground. It’s cheap insurance.

Hot to Neutral

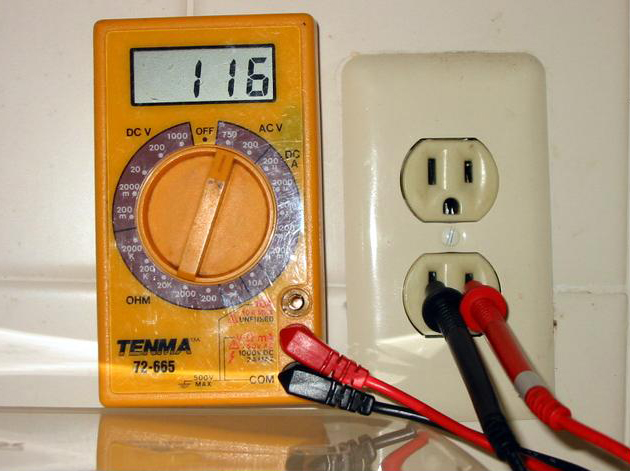

With nothing plugged in to the wall outlet, switch on the 20-amp circuit breaker at the power panel, set your meter to the 200 or 750 V AC setting and using one hand insert your meter leads into the left and right neutral and hot slots.

Remember not to rest your opposite hand on the metal box, as that can cause a shock through your heart if something goes wrong. That’s why electricians traditionally stick their unused hand in a back pocket.

It really doesn’t matter which side of the outlet gets the red or black meter lead since it’s alternating current (AC).

Since the neutral connection is at 0 volts and the hot connection should be around 120 volts, you should read somewhere between 115 and 125 volts on the meter display. If not, then something’s wrong with the power hookup.

If you measure 0 volts, then maybe you need to reset the circuit breaker, or if you have an outlet with a GFCI, remember to push the little reset button on the outlet itself. If it still doesn’t measure 110 to 125 volts, immediately contact the stage manager.

If you measure 220-250 volts, then that power outlet has been rigged inside the circuit breaker box to produce higher voltage. This is illegal and highly dangerous as you’ll surely blow up every piece of electrical gear you plug into the outlet. So, if you read 240 volts on the 120-volt outlet do not plug in your amp, and, again, immediately contact the stage manager.

Hot to Ground

If hot-to-neutral checks out around 120 volts (110 to 125 volts), then it’s time to test the ground, so plug one meter lead into the hot (shorter slot) and the other into the ground (U-shaped hole) connections.

Since you’re reading from the ground connection, which should be 0 volts (less than 2 volts), and the hot connection, which should be around 120 volts (110 to 125 volts), your meter should show about 120 volts.

If you read 0 or something strange such as 60 volts, then the ground wire might be floating, which could cause a hot-chassis condition that will shock you when touching the strings of your guitar and microphone.

Neutral to Ground

Next, check from neutral to ground. That should read very close to 0 volts, but up to 2 volts is acceptable according to the electrical code.

If, however, you read around 120 volts from neutral to ground, then the polarity of the power outlet is reversed. Don’t plug in. Again, this can cause a dangerous hot-chassis condition depending on how your guitar or PA system is wired.

Final Exam

As a final check, a run-of-the-mill outlet tester from your local home center will confirm that the polarity of the outlet is correct.

Plug it into the power outlet on stage and you should see only the two yellow/amber lights light up. If you see any other combination, do not plug in your guitar amp. Once you’re familiar with the procedures, all this can be done in a minute or two.

It’s a very small inconvenience that will help ensure the safety of you and your band.

Stay safe!

Quick Tips

—Always set your meter to read AC volts using the 400-, 600- or 750-volt scale

—Hot (short slot) to neutral (tall slot) should read approx 120 volts (between 110 and 125 volts AC)

—Hot (short slot) to ground (U-shape) should read approx 120 volts (between 110 and 125 volts AC)

—Ground (U-shape) to neutral (tall slot) should read approx 0 volts (less than 2 volts AC)

This article is provided as a helpful educational assist with sound system setup and musical performance, and is not intended to have you circumvent an electrician or qualified audio technician. The author and the HOW-TO Sound Workshops will not be held liable or responsible for any injury resulting from reader error or misuse of the information contained in these articles. If you feel you have a dangerous electrical condition in your PA system or instruments, contact a qualified, licensed electrician or audio installer.