When most people think of sound reinforcement systems, or audio systems in general, they rarely do so with regard to speech intelligibility (SI).

It’s usually about the music, with the assumption that if a system sounds good for music, it should work for speech.

While this can be true in small, well-behaved rooms, it is seldom true in large spaces.

My first sound system disaster was the design and installation of a large, expensive sound system that failed to produce acceptable SI. Its excessive excitation of the room was lovely for the choir and symphonic music, but a talker at the lectern was unintelligible at all but the closest seats.

I quickly exhausted the “quick fix” solutions to no avail. These included equalization, re-aiming the loudspeakers and trying a different microphone.

It became painfully apparent that I had placed the wrong loudspeakers in the wrong place, and no amount of signal processing could change that. I found a copy of Sound System Engineering by Don and Carolyn Davis at the local electronics store. As I methodically ingested it I found that I had broken most of the rules for maximizing SI. I fixed the system at my own expense, and was determined to never again design an unintelligible sound system.

In short, as a contractor I had some of the pieces of the puzzle, including basic audio knowledge, lots of tools and some equipment franchises. I knew the makes and models of all the popular mixers, amplifiers and loudspeakers. Until that project, my musician background had always enabled me to tweak my systems to make the musicians happy. I considered myself a pro.

What I didn’t have was an understanding of the science behind the sound. When it comes to SI, you leave the touchy/feely world of music “quality” and are left with the cold, hard variables of communication theory and principles.

Clearly, the way to avoid repeating the same mistake was to:

1. Learn the principles that govern SI

2. Develop a system design workflow that places SI at the forefront, rather than making it an afterthought.

Additional Skills

In rooms that are reverberant, or excessively “live,” achieving acceptable SI requires a special skill set.

These include:

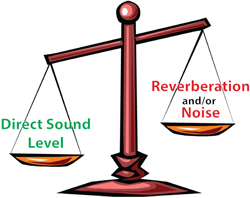

1. An understanding of the variables that determine the direct-to-reverberant energy ratio at a listener position. These can be understood (in an ideal sense) through the Hopkins-Stryker equation.

2. An understanding of what constitutes a “reverberant” sound field, and how a reverberant space differs in principle from a “live” space.

3. An understanding of the role of loudspeaker directivity and placement with regard to the establishment of the direct-to-reverberant sound energy ratio. I had always thought that the loudspeaker’s sensitivity and power handling were its most important specs. Regarding SI it’s more important to consider its directivity index (DI) and directivity factor (Q)—ratings I had always ignored on the spec sheet.

4. An understanding of what matters to the human hearing system with regard to SI. It’s not just about “sound quality.” Ironically, a sound system can be intelligible and not sound good. The cell phone is a notable example.

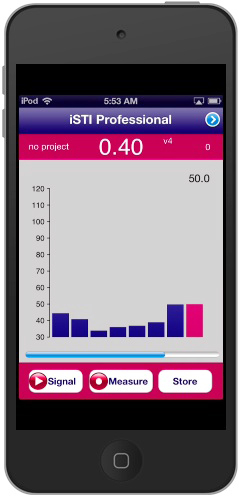

5. An understanding of how to quantify SI through measurement. While we don’t have meters that measure “music quality,” we do have meters that measure SI.

6. An understanding of how to estimate SI at the drawing board, including what room acoustics computer models can and can’t tell you about SI.

7. Your customers cannot purchase SI at a big box store or on-line. They need YOU, not just the gear that you sell. Costco will never sell SI.

It should be noted that one can have years of experience “doing sound” and not develop competence in these areas. I was proof of that.

Expanding your skill set can give you a bright future as an SI professional. Why bother?

1. There is a LOT of competition for music playback systems, resulting in low margins and the risk of being lost in the crowd. It is not likely that your competitors understand how to design systems that are intelligible, and fix systems that are not.

2. Music is subjective by nature, with no absolute reference or performance benchmark. There exists no objective test or measurement to prove that a system “sounds good.” This can make it difficult to resolve customer complaints. I was once told that a system I designed lacked “warmth.” I was tempted to set the loudspeakers on fire.

3. SI can be assessed by listening tests, PC-based measurements, and even hand-held measurements. SI can be scored to quantify how one loudspeaker system compares to another.

4. There is a basis for declaring a speech system “finished,” where it seems that music systems are constantly needing another tweak, effect or the latest wiz-bang processor.

5. There are codes and (pending) laws requiring that emergency evacuation systems be intelligible – not so for music systems. The architect of a space may have to capitulate to the sound system designer if adequate SI cannot be accomplished due to the room’s background noise or acoustics.

6. The principles and practices that govern SI are timeless. They have not changed for a century, and will not change in the future. Signal processing can only remedy some of the causes of poor intelligibility.

Music systems are like art galleries. Speech systems are like road signs. One evokes an emotion, and the other conveys information. It is important to make the distinction.

Path To Competence

SI in sound reinforcement systems lends itself to scientific investigation. There is science behind the sound. I outlined the required skill set earlier in this article. How do you get there?

Fortunately you have more options that I did nearly 30 years ago. Trying to glean this stuff out of textbooks is challenging, to say the least. Synergetic Audio Concepts offers some resources to shorten the learning curve. These include:

Web-based Training Programs

Our “Sound Reinforcement for Designers” web-based training was developed with the speech intelligibility professional in mind. It covers basic room acoustics, loudspeaker directivity, and how to measure and predict SI.

It doesn’t replace product-specific training, such as for a room modeling program or measurement system. What it will do is help you use these tools more effectively. You can find a complete description at www.synaudcon.com.

In-Person Training

In addition to online audio training, SynAudCon offers in-person audio training. These classroom-style events include instruction by some of the industry’s brightest and most talented audio practitioners and professionals. Attendees will see best audio practices demonstrated and applied to contemporary audio systems.

Universal Principles

Knowledge gained about SI will apply to every sound system that you design or modify, not just those that might be used as an emergency communication system (ECS). My approach to a sound system design is to first design for SI. This necessitates loudspeaker selection and placement that assures a dominant direct field level in the speech octave bands at all listeners. If the system will also be used for music, its bandwidth can be extended accordingly.

The natural law of the universe dictates a progression from order to disorder. You can’t unscramble eggs. Design for speech first, since speech systems have more stringent sound energy ratio requirements than music systems.

Conclusion

My sound system design disaster from the 1980s may have been the best thing that ever happened to my audio career. It made me aware of viewing sound system design as a science rather than as an art. This, in turn led me into the world of acoustical measurement instrumentation.

While our tools of yesteryear pale in capability when compared to those available today, the principles governing their use have not changed at all. Direct your training endeavors toward concepts that are timeless. These will be around long after today’s latest, greatest mixer finds a permanent home in a museum.

More Church Sound articles by Pat Brown on PSW:

How To Illuminate The Audience With Beautiful, Consistent Audio Coverage

Proper Loudspeaker Placement: How To Avoid Lobes and Nulls

Ten Reasons Why Church Sound Systems Cost More

What Makes A Quality Loudspeaker?