Florence Welch was exquisitely graceful at London’s O2 Arena in late January, her red hair flowing against an off-white dress as she descended from the ceiling in a framework of chandeliers lit by glowing candles. Opening one of eight shows in the UK and Ireland that were rescheduled late last year after she broke her foot onstage during Florence and the Machine’s Dance Fever world tour, she launched into Heaven is Here, her voice powerful and alluring as she floated across the length of the stage, spun, and jumped, all seemingly in unison with those filling the arena.

Combining dance with song, Welch acts out her lyrics. Her music plumbs depths of meaning, and naturally relies heavily upon bringing every note to the crowd with rich clarity and emotional impact.

“Our goal is to insure that nothing goes unheard or unappreciated,” says front of house engineer Brad Madix. “It goes without saying that first and foremost people come out to hear Florence’s voice and see her perform, but beyond that there is an element of sound design that has a very real presence within these shows. It’s the things that aren’t always overtly integral to the music that make the texture of the mix more interesting – unusual horn tracks, percussive toys, and a wide range of other sounds.

“I like to reproduce these sounds to whatever degree I can, it’s these nuances that make the mix come alive. Sometimes it’s a challenge to find a place for them all, but in the end well worth it.”

The tour completed its rescheduled shows from last year in early February in Dublin. Next up is Perth, Australia in early March, and then the show embarks upon a series of dates that will span Oz and New Zealand prior to appearing on the international festival circuit.

The Approach

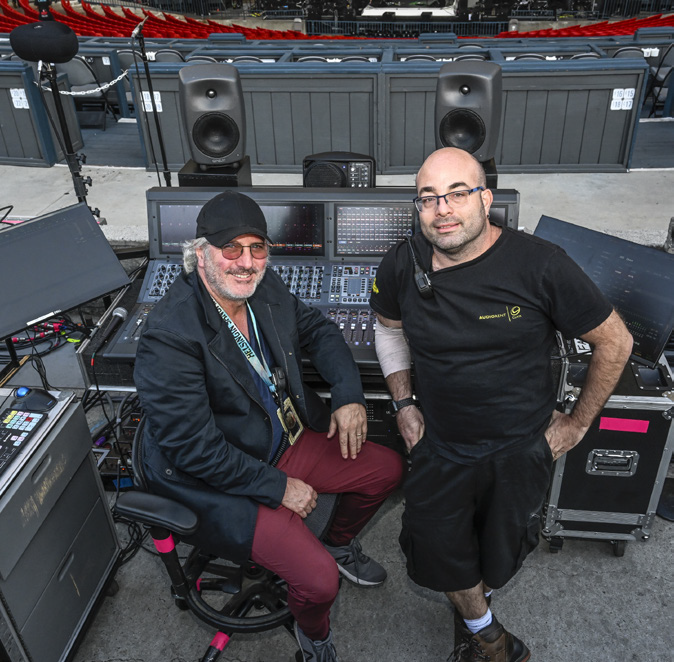

Besides Madix, the audio crew includes monitor engineer Hannah Brodrick and systems engineer Elad Kleiner. With Clair Global providing sound reinforcement elements in both the U.S. and abroad, the main and side arrays have typically include 16 Cohesion Series CO-12 enclosures each, while the rear housed eight CO-10s. Subwoofers are flown and placed on the ground, with both locations utilizing six CP-218s each. Most recently a half-dozen CP-6 boxes stood-in as fills across the front.

Networked with Dante with analog backup, the system has proven itself in a R-L-R-L (side-main, main-side) configuration. “We’ve always had great success with the Cohesion Series,” notes system engineer Elad Kleiner. “It flies quickly, is easy to rig, lightweight, and most importantly, is capable of far-reaching throws. We can do most arenas without a need to carry any delays or rely heavily upon house delay systems. Using a Lake control platform provides us with plenty of flexibility on both a tuning and operational basis via a touchscreen interface.”

Designed as a full-range system with its flown subs getting a R-L feed to extend the lower octave of the main hangs, the rig’s earth-dwelling subwoofers are run an octave lower than their airborne counterparts in “ultra-low-frequency” mode to bring more punch to content from drums and electronic components.

Based upon the needs of each venue, Kleiner chooses a voicing curve to tune the PA with. In order to build the low-end to proper levels, the box count is determined according to the number required to provide the proper coupling. While tuning the PA to the voicing, Kleiner and Madix will add an overlay of shaping EQ designed to aid the process of adjusting the fine details and nuances as they move from listening to reference monitors to the large format PA itself.

“For the tuning process I use Tuning-Capture from WaveCapture,” Kleiner adds. “For monitoring during the show we use [Rational Acoustics] Smaart 8. Using overlays of EQ for our shaping is quite helpful when it comes to comparing and adjusting our overall system voicing and making sure it will translate into the mix properly with the same consistency every night.”

Madix employs an Avid VENUE S6L desk to manage his house mix. “The only additional gear I keep at front of house is a Waves SoundGrid server,” he points out. “I use a handful of Waves plugins and a smattering of others from McDSP. I’d been a Profile user, but when the S6L came out I made the switch. I like the sound of the new desk, I feel it was a big upgrade for them. As an early adopter, I really didn’t have a lot to choose from in terms of plugins, so I forced myself to get the most I could from out of the desk.

“Honestly I found most of everything to be either pretty good or a lot better than I expected. In no time I got to be very proficient with what the package came with, and did the whole last tour with Florence on it. That mindset carries over to today, I’m still keeping things pretty Spartan.”

Among the Waves plugins he keeps at hand, Madix finds the F6 floating-band dynamic EQ to be a natural for Florence’s vocals as well as backing vocals. With six adjustable parametric filter bands each outfitted with compression/expansion controls plus mid-side processing options, according to Madix the F6 brings more precise capabilities to the matter of carving out space in a busy mix.

Conversely, he calls on a CLA-2A comp/limiter to help tame percussion and a McDSP 6050 that’s stuffed to the brim with modules that fall under a gamut of compression dynamics control he can use to manage attack and release times, ratio, threshold, and more.

Going Further

The show is recorded live every night with the intention that it could be used for some type of post-production, and as Madix tells it, “sometimes it is.” In fact, tracks recorded to Pro Tools from his S6L were used to create the double vinyl album Dance Fever (Live at Madison Square Garden).

“The funny thing is,” he adds, “the first shows we did were what we call underplays – smaller shows that included City Hall in Newcastle as well as a small theatre in London. We did them just to get out in front of people and create some buzz. I woke up the morning after the first one, tested positive for Covid, and couldn’t go in for the next. Fortunately our production manager Mark Woodcock is also a sound engineer so he was able to fill in. Then the keyboard player got sick, and so did the violinist.

“I was able to cut the stems for each musician and put them on a USB key without coming into contact with anyone. Then the stems were dropped into playback and brought up as separate channels for each musician. In theory if you turn those channels up you should have them in the box. At the moment of truth everything did indeed line up and it worked! We have never had to do that again since, but now it’s always something that’s there if we need it.”

Madix estimates he’s built a “few hundred” snapshots for the show, some of which adjust stems from Welch’s records. “Know, however, that even if a stem is made exactly as you hear it on a record, it’s never 100 percent there when you take it to a live show,” he notes. “For reasons I don’t think anyone fully understands, when you are presenting it through a PA to an audience you need to add a little more drama to it.

“A manager of a band I was working for once told me that my job was to make things sound better than the record. He wasn’t wrong. The point is to make your sound more appropriate for a live audience, and that often entails making things even more obvious.”

Switching Gears

With Florence Welch orchestrating things out front, her supporting band includes Rob Ackroyd on guitar, Loren Humphrey on drums, Tom Monger on harp, Dion Douglas on guitar, violin, and backing vocals, Aku Orraca-Tetteh on keys/backing vocals, and bassist Cyrus Bayandor.

Working from a DiGiCo Quantum 7 console with 32-bit DAC cards, monitor engineer Hannah Brodrick brings the band’s personal mixes to life with the aid of a Shure PSM 1000 personal monitoring system. She additionally keeps a DiGiGrid MGB interface and Logic Pro at hand for multitracking, while Florence’s vocals carve a signal path to her Quantum 7 with the assistance of a Shure AD2 wireless stick outfitted with a DPA d:facto 4018V capsule. Within this realm, RF management falls under the guidance of Shure’s AXT600 Axient Spectrum Manager and Wireless Workbench.

“As far as the console goes,” Brodrick explains, “in my opinion there is nothing else that quite compares to DiGiCo when it comes to flexibility. I’ve never had a situation yet where I haven’t been able to make a macro for some totally unique command with several functions. We’re currently running around 85 channels for this show with eight separate guitar channels, so having the space with three fader banks is essential for me to be able to focus on several layers at once.”

The PSM 1000 system was a logical choice based upon its audio quality and robust RF performance, she states. “We need everything the system offers,” she admits without hesitation. “Florence usually runs out to the house mix position and sometimes even further during a show. Since switching to Shure I haven’t ever had a drop-out or had to chase behind her with an antenna. We tried out a few different mic capsules during rehearsals and in my estimation the DPA 4018V was best suited for her voice. It can handle the delicate nuances of a whispered line all the way up to the full SPL of an anthem without any distortion, and most importantly I can keep an eye on it along with everything else via Wireless Workbench.”

Brodrick employs a lot of snapshots for click-level changes as well as other nuanced things. “A couple of songs have six to eight snapshots each,” she says. “I automate these via timecode. There are a number of songs that segue into each other, and being able to automate slow, barely noticeable changes between snapshots is great, particularly when a guitarist is holding out a note – you don’t want that to quickly disappear or get louder in his ears as the next song begins.

“I’m pretty deep into the recall scope with different rules of what can be saved and recalled between songs, snapshots, and then overall. Many channels, such as ambients and guest vocals are in safe groups because those are really the only variables on any given night. I use mute safes on Florence’s vocal channels because a lot of soundchecking is done without her. More to the point it’s a safety thing: Then I know if I save a snapshot where her mic is muted there’s no danger of it being recalled halfway through an actual show.”

Providing Space

Each musician’s mix is vastly different, a fact that has lead Brodrick to generally steer away from applying her own ideas about how things should sound beyond basic EQ and dynamics. In providing the musicians with plenty of space to make their own sonic choices, she has even gone to the extreme of letting them adjust their mixes themselves from her own console – under a watchful eye of course.

“I multitracked every show and rehearsals before I knew exactly how everyone wanted their mix,” she says. “Then I invited the musicians to listen and adjust things themselves from my desk if they wanted to. They really appreciated being given the space to experiment, and it really helped us build a mutual understanding of how we wanted to get things done.”

Among all her duties, Brodrick also confesses she’s as much a switchboard operator on this gig as she is a monitor engineer at times. “Each musician has a mic and Radial HotShot microphone switcher, and every tech has a talkback,” she points out. “I use a lot of macros and matrixes to make sure everyone can hear the right people at the right time and don’t wind up hearing the wrong people at the wrong times.”

Dressed in their own flowing clothing, floral headpieces, and wearing extravagant makeup, the crowds out front know little of any of this, of course, and probably shouldn’t care anyway. As the songs transition from emotional ballads to group sing-alongs where everyone knows the words, theirs is a roller coaster ride where if all goes right the audio is intelligible at all times, uplifting, and even transcendent. “See it, hear it, and believe it,” one fan said in an online review. “And catch it now because it’s an experience to remember.”