Sometime in the fall of 1984, I was told that I was slated to do a concert for Dame Vera Lynn, in the round, at the London (Ontario) Gardens Arena.

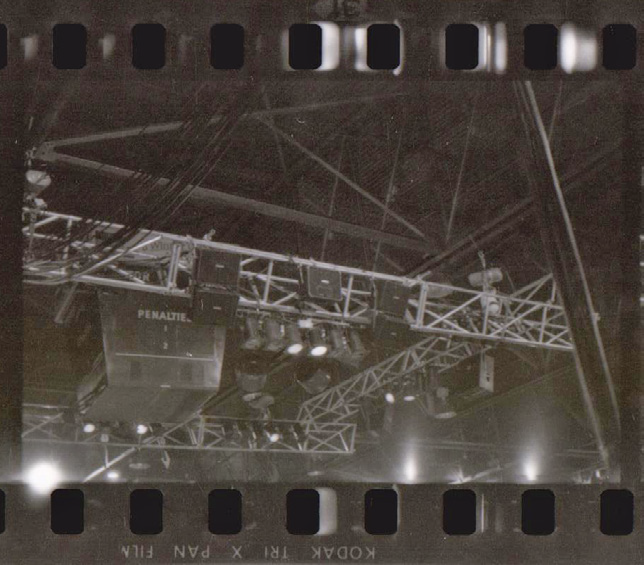

I was also handed a crude sketch of what the PA would look like, flown over the stage on our fly rig of the day. This consisted of two massive aluminum beams, called “Strongbacks,” supporting a platform with our standard ground-stacked concert PA stacked and strapped on top of it. That system consisted of our own design 15-inch folded horn subs and 12-inch horn-loaded midrange cabinets and Community radial horns with Altec drivers topped with Electro-Voice ST-350A tweeters.

I took one look at the drawing and said, “Nope, I’m not doing that!” But, I was still doing the gig, so I set about designing my own rig.

Figuring The Configuring

First, some background information. Dame Vera Lynn was the voice of World War II for virtually all service veterans of the Commonwealth countries (i.e., England, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, etc.). Her popular songs “We’ll Meet Again,” “(There’ll Be Bluebirds Over) The White Cliffs of Dover” and many others were the soundtrack that many had danced, fought, and, if they were lucky enough, came home to.

Second, I had spent the summer of ’84 doing an Ontario wide arena tour, a piece of thinly disguised provincial government propaganda called “The Bicentennial Showcase” that was truly horrible enough that it may well get its own Road Story at some point in the future.

There were many reasons why it was horrible, but my main issue was trying to get a decent sound in mostly empty hockey arenas. The “it’ll sound better when the kids fill the seats” thing really was a thing back then, and we couldn’t fill the seats. The crazy thing was, we had a cast that could have filled every one of those arenas, but none of their names were on the “montage-style” promo poster because the government would have had to pay them all more if they were named.

The PA for that tour was our first attempt at a four-way, all-in-one cabinet (two per side) and two flown centerfill cabinets. I’d designed the rigging for these two cabinets, a pair of EV PI-1503s, which became the first flown loudspeakers in the company’s inventory.

Now at first blush, these Permanent Installation versions of EV’s popular S-1503, which were made of particle board or maybe MDF (or, as I like to put it, “hope and good intentions”) were not a good choice for anything to be flown. However, I added internal steel angle bracket bracing to all four corners, which was then tied to the rigging track (the same stuff that’s used for load bars and straps in semi-trailers, and no, I wouldn’t use it again…), and then the entire box was wrapped with marine fiberglass so they were plenty strong enough to be suspended as single hangs (i.e., nothing else ever hung from the box).

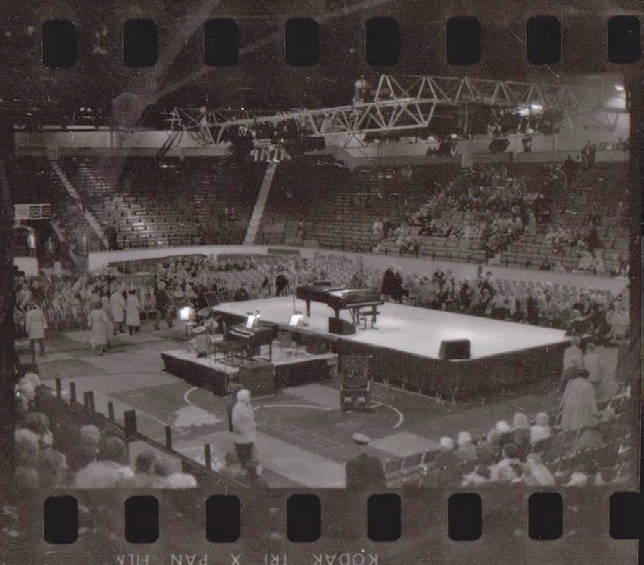

So, armed with the knowledge that our larger PA offerings sounded awful in an arena for a “family style” show, and the fact that I had two cabinets that I knew I could hang from the box truss we were going to fly over the “in-the-round” stage (which was really a rectangle in the middle of the arena floor), I set about coming up with the rest of the rig.

This ended up consisting of 10 Yamaha S250X two-ways (2 x 8-inch and 1 x 1-inch HF) to fly from the truss, two stock EV S-1503s that I suspended with three-inch load straps, and the aforementioned two PI-1503 (rigged) boxes. The Yamaha cabinets flew from yokes and clamps, with eight of them bolted together in pairs of two with more angle bracket. All those boxes had passive crossovers.

Amplifiers were probably QSC A series and a pair of 3500s, as I was partial to QSC, and none of these were permanently assigned to any of our PA racks at the time. Control would have been a graphic EQ or two and probably a couple of compressors. I don’t recall the console but it would probably have been either a Yamaha M916 or a Soundtracs SR24-4-2, which was a flat, built-into-a-road-case-type desk. The latter console was quite nice for the day, clean and quiet with musical sounding EQ. (For those who don’t know, Soundtracs evolved into DiGiCo sometime in the last 1,000 years or so).

It’s Never Straightforward

The drill for the gig was the same as the Roy Clark show that I detailed in a previous article – drive out the night before, get a hotel room and be at the venue for an 8 am call. When I did walk into the arena, I was instantly glad to see that I had kiboshed the proposed “PA-on-a-flown-platform” idea as the time clock was already hanging over the stage and flying the platform would have been a) incredibly difficult, and b) left very little clearance.

We had an efficient local crew so the load-in went smoothly. However, when we began assembling the box truss that both audio and lighting were to hang from, there was a snag.

At the time, we were using a folding triangular truss (Thomas brand?), which was great for truck packs (since it folded flat) but it required the use of “spreader bars” to hold the two folding parts in position, and unfortunately, the “lampies” had forgotten to put the bars on the truck. This little error had the potential to leave us dead in the water for a minimum of two hours, assuming they could get hold of somebody to go to the shop and drive them out to us… on a weekend.

Of course, I wasn’t happy with this possibility, so after looking the situation over, I came up with a workaround. Truss corners were either not a thing in 1984 or we simply didn’t own any, so the plan for this rectangular box truss was to fly the two short end sections, and then suspend the longer sides underneath. The two sections of truss were to be joined together with double Cheeseborough clamps, four in each corner.

My plan was to float the end sections high enough to get the sides underneath them, and then use the clamps to a) clamp them together (as planned), and b) spread the angle sections to the proper width while we waited for the spreader bars to arrive. (In case you’re having trouble picturing this, the end sections were flown angle-side up, like the letter “A,” and the side sections were flown angle-side down, like a letter “V,” so the two flat sides met each other where the clamps joined them.)

My recollection of how this worked out is that the lighting folks and the riggers did such a good job of approximating the correct degree of angle that when the spreader bars did finally show up, they all just clipped into place without having to adjust the width.

In any case, this workaround allowed us to float the truss at working height and cost us almost no time at all, so the set-up went along pretty much as planned. I flew the PA with a loose cluster of five of the Yamaha boxes in a 2-1-2 configuration in the center of the long sides and the EV boxes on the ends of the truss. I notice from the photos that I took at the time that even back then, I favored hanging boxes that were tasked with nearfill coverage horn down, something I still do today.

Because the show was “in the round,” there wasn’t a logical place for front of house (i.e., the mix position) to be located, so we ended up with all three control positions (FOH, monitors and lighting) side-by-side on one of the player’s benches on one side of the arena.

I don’t recall much of the rest of the day, but I would have EQ’d the PA and set levels to balance the mixture of boxes and locations. I also don’t remember incorporating any delays into the set-up although I know that at that point we owned a Yamaha YDD2600 (one of the first multi-output alignment delays) and a dozen or so D1500s that we had purchased for the Papal Mass back in September (another article!). I do know, however, that in November ’84 I was still about eight months away from my own personal “discovery” of the Haas effect, so delay probably wasn’t on my radar.

Musically, there was a grand piano up on the deck, with lid down, so it probably had one or two PZM microphones taped to the lid as was the practice of the day. Next to the stage on a low riser was a small pit band consisting of bass, keyboards and a cocktail drum kit.

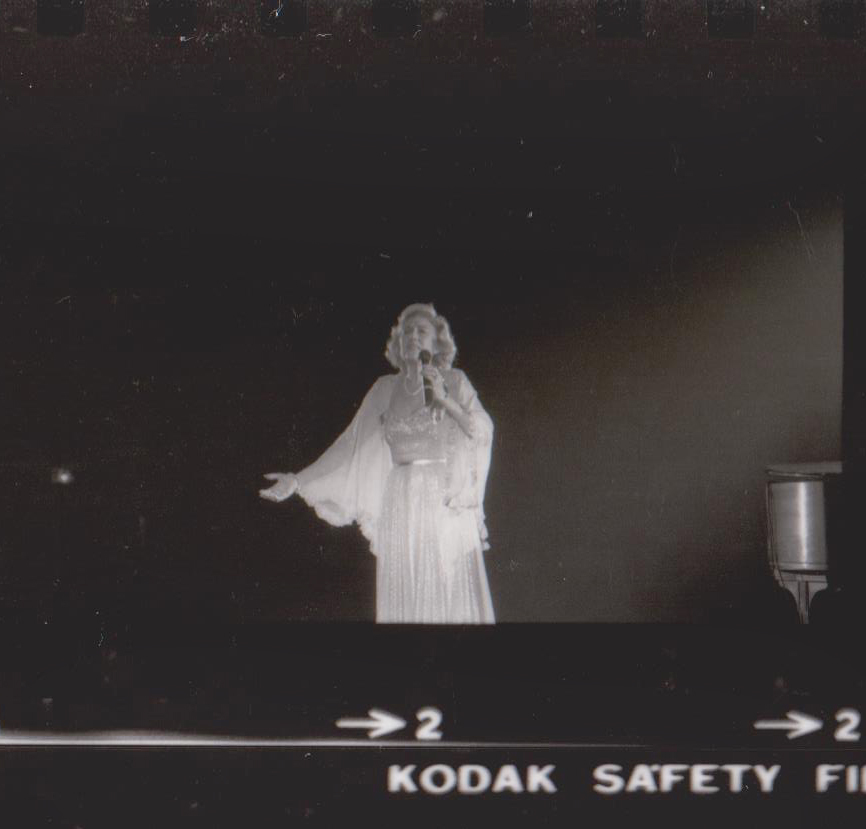

There was a wireless microphone – probably a Telex system – for Dame Vera’s vocal, as well as a hard-wired spare that may have been an AKG C535. We definitely didn’t see (or hear) her before the show.

All’s Well

The crowd was probably 100 percent veterans and their spouses, with many of the veterans in their uniforms, a stirring site. Comedian Jimmy Kennedy opened the show… I still remember one of his jokes almost 40 years later. [Mother Superior and a young nun take the convent car into town to buy some supplies. On the way home they experience car trouble and consequently get home very late and find the convent closed and locked for the night. Undaunted, they decide to scale the walls. Halfway through this exercise the young nun exclaims “Oh, Mother Superior, I feel like a commando!” to which her nibs replies, “Don’t be so foolish, girl! Where are you going to find a commando at this time of night?”]

There was a brief intermission following Jimmy’s set, towards the end of which Dame Vera’s husband/manager limped over to our position on the player’s bench, wearing a beret and a Royal Air Force blue blazer, and said to us: “If she’s not comfortable up there, she’ll do 20 to 25 minutes, sing the songs that they’re all expecting to hear, and call it a night. If she is comfortable, there’s no telling how long she’ll go.”

He then produced four crisp $20 bills and proceeded to slide one across the boards to each of us (the dimmer tech was sitting next to the LD). This was the second of two times that I’ve been tipped prior to a show, so I can happily say that after 42 years in this business I am up $40 on tips.

I’m also happy to report that Dame Vera took the stage and stayed there so long that I was beginning to worry about the battery in her microphone. She was 67 at the time and had more than 50 years of hits to choose from. And the sound? Amazing, if I must say so myself.

It was certainly the best-sounding arena show that I’d done that year and still ranks as one of my best ever. The show was a pleasure to mix, with the only sonic issue being a squeaky hi-hat pedal. And, yes, I did get into the “roadie crouch” and run out there with a can of WD-40 to try to fix it, and no, it didn’t work.

Why did it sound so good? My theory that I’ve long held, is that instead of “moving air” as some people like to call the art of doing sound, sometimes you have to kind of sneak the soundwaves through the air while moving as little air as possible. Put another way, keeping the volume low enough and the frequency spectrum (e.g., the low end) somewhat constrained to avoid exciting the room’s acoustics.

About 10 years later, when I was back managing the company (I had quit not long after this gig, for a myriad of reasons), I was talking to a potential client on the phone when he mentioned that his business was promoting concerts for veterans. I told him about mixing the Dame Vera Lynn show and he said, “That was you? That was my show, and to this day it’s still the best sounding one we’ve ever done!”

Further discussion revealed that, not long after this show, he had shifted his focus to doing these shows in the U.S. instead of Canada and had used other providers because he assumed we couldn’t work in the States. I assured him that wasn’t the case, handed him off to one of our account managers and we ended up doing several more shows for him.

So, doing the job right did lead to some repeat business, it just took a decade for it to happen.