In a continuation of my previous article (here), I’m taking a look at five more of the most common live mix mistakes I’ve encountered when attending gigs as an audience member and offering some potential solutions to these everyday issues.

Excuse me while I kiss this guy. It still surprises me when I go to gigs where either the vocals can’t be heard or they’re so buried in the mix that it’s impossible to make out what they’re saying.

The vast majority of music performed by bands at gigs is song-based, and arguably the most important element of song-based music is the lyrics. So if they can’t clearly be heard above the band then the full artistic vision of the artists is not being adequately conveyed – and that’s often the fault of mix engineers.

We all know that there’s a limited amount of gain that can be applied to any given microphone before feedback is inevitable and there’s no magic solution to this issue, but there are a number of things that can improve the chances of getting the vocal heard.

The battle against feedback starts at the very beginning. The positioning of the loudspeakers and the initial reflections can have a huge bearing on this issue, so try to keep microphones behind the main loudspeakers and exploit the polar patterns of the mics to best position any monitors.

The tuning of the PA can also help you out. I always ring out the system using the vocal mic placed in the most likely position it will be in during the show, but if I anticipate a particularly troublesome room, then I EQ more extremely than a properly treated room (that has decent separation between the stage, the room and the PA).

If you’re doing monitors from front of house, try cloning the main vocal (using either a Y lead or via soft patching) and treat the copy sent to the monitor with less EQ and compression than the copy that’s going to the PA. Another classic trick is to invert the polarity of the vocalist’s monitor send, as this will invert any standing waves and might just shift a troublesome frequency out of the mic’s path.

You’re miking up the floor! This is a common issue and most of us (me included) have been guilty of perpetrating it at some time. The situation is as follows: you have limited resources and the band just turned up with a full horn section that no one warned you about and now you’re short a mic stand or two. So you have a bright idea: “What if I take the stand on the guitar amp mic and wrap the cable round the handle so the mic dangles in front of the amp? Brilliant!”

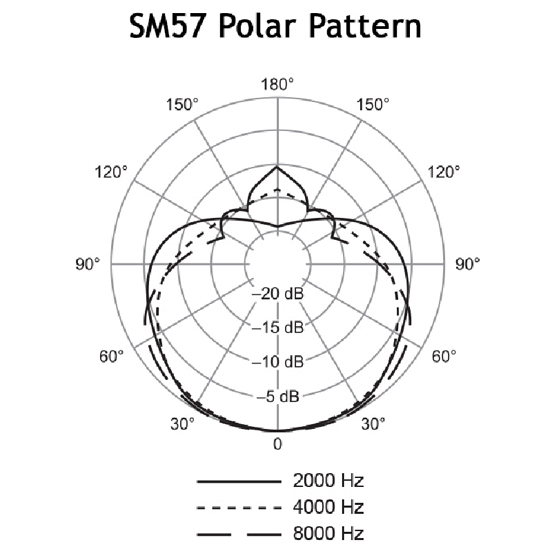

To find out why this is a bad idea, you only need to look at the polar pattern of most mics commonly used on guitar amps. Any signal entering the side of a Shure SM57, for instance, is going to be 6 dB quieter than if it were the same distance from the end of the mic – and that’s at 2 kHz. As the frequency increases, the sensitivity drops off to -10 dB (at 4 to 8 kHz). Therefore you’re getting a weaker signal which means inevitably having to increase the gain and thus increasing the risk of feedback.

In addition, you’re getting a less consistent frequency response because the end of the mic (i.e., where the signal should be) is pointing down at the floor, so in effect you’re miking up the floor. I once saw an engineer do this while the guitar amp was sitting on top of the bass amp and he couldn’t figure out why the bass was still so loud, even when the bass channel was off!

The engineer’s best friend can help us out when we’re short of mic stands; yes, I’m talking about gaffer tape. Drummers often have too many cymbal stands so they can easily be pressed into service as impromptu mic stands, and I’ve even taped mics to chairs in the past – it might not look pretty but it sounds much better than miking up the floor.

All I can hear is guitar. This ties in with my initial point, as one of the most common causes of not being able to hear the vocals is that the guitars are too loud.

Guitarists are a key part of most genres of music, and it takes a certain amount of skill and practice to get to the point where they can get up on that stage and show the world what you can do, but unfortunately, it also takes a fair amount of ego. Guitarists like to be loud not just so they can hear all of the intricacies of their playing but also because they like to be loud.

I once worked with a guitarist who had a very expensive amplifier that he cranked up so loud that you couldn’t hear anything else – not the drums, the bass or any of the other instruments; the mix was just guitar.

So I asked him nicely to turn it down and he proceeded to explain why this particular amp only sounded good when the level was above a certain point. I tried to explain to him that at those levels all the audience will hear is the guitar and I swear he smiled. (That was clearly not the correct logic to use on a guitarist.)

This particular problem gets worse the smaller the venue. Not only can the guitar dominate the mix if the amp is too loud, but the directional nature of guitar amplifiers means the mix can be drastically different depending on whether you’re standing in front of it or off to the side.

The best way to avoid the problem is to work with the guitarist during sound check to get the appropriate levels. One of the most common causes is guitarists not being able to hear themselves, so I always raise up the amp and make sure it’s pointing at the guitarist because no one has ears in the backs of their knees.

If that doesn’t help, I make sure they get plenty of level in their monitor – you can actually get a guitarist to turn down their amp by increasing the level in the monitors (although it doesn’t always work). Many musicians aren’t even sure of the appropriate level for their amps on stage, so I always advise them in small venues to set their amps at a level so they can hear themselves clearly over the drums, but no more, and then leave the rest to me.

If, however, you’re faced with the kind of guitarist who refuses to turn down the amp because it compromises the purity of it’s tone, then it’s time to introduce him to the concept of a power soak.

Terrible troubleshooting. I was at a gig where the band was about to go on and the customary line checks were being performed. It quickly became apparent even to the unknowledgeable onlooker that the signal from the SPD drum sampler was not reaching the desk.

The engineer proceeded to kick the DI box, pull the XLR cable out and put it back in again, prod the SPD, fiddle with some controls, and generally stand and stare with a puzzled look on his face, all this while repeatedly returning to the desk to see if the signal had magically re-appeared. The whole process took about 20 minutes and never got resolved, so the band played on without their trusty drum samples.

Basic troubleshooting skills are a vital part of sound engineering and can mean the difference between a smooth-running night that everyone involved enjoys and the kind of hellish experiences that get discussed in hushed tones wherever engineers gather.

There are two distinctly different approaches to troubleshooting, the choice of which depends on whether it’s pre-show or in-show mode. If in pre-show mode, such as sound check, you can rather leisurely troubleshoot any issue by logically following the signal chain and swapping out consecutive components until you’re able to isolate and replace the faulty item.

However, if you’re in show mode there’s no time to methodically inspect the signal chain, so the best option is to duplicate it. Plug a new XLR into a different channel on the multi-core which goes to a different channel on the console, and plug that into a different mic or DI, swapping out the whole lot in one fell swoop.

Nine times out of 10 it will work perfectly well and you can just carry on; if it’s an analog desk you’ll need to copy across the channel processing, but if it’s digital you should be able to soft patch the input so the new signal comes up where the old signal should have been.

Too much track. This isn’t technically a mistake but something of a personal bugbear that I think we should all be a little wary of. More and more bands are using backing tracks live, partly due to the fact that it’s so much easier to take a laptop on stage, and also because it cuts down on musician costs and enables bands to produce a bigger sound on a small budget.

However, we should never forget that the audience is there because they’ve (usually) paid to witness and participate in a live event. Few people turn up expecting to hear the music rendered note perfectly – if that was the case then most would stay at home and listen to the album on their hi-fi (and avoid all of the overpriced beer).

So when bands deploy too much track featuring ghost choirs and invisible horn sections, I find it detracts somewhat from the live experience. It also breaks a kind of unspoken agreement whereby we don’t mind if they use track elements to enhance the show as long as it doesn’t overshadow the live dynamic.

It’s a fine line and I’m aware that not everyone will agree with me that too much track is a bad thing, but I do have a little advice for how track elements should be mixed. The key is to get the live elements sorted first, get the band rocking along, and then add the track elements subtly to support and enhance the band. If you do it right, most people in the audience won’t even realize that backing tracks are being used – they’ll just think that the musicians on stage are incredibly talented to create such a big sound.

I hope that my observations have helped not only identify some of the most common mix mistakes, but also provide some useful ways to potentially deal with them. Remember that to err is human but to not learn from your mistakes, or those of others, is downright foolish.