Of course, it’s the responsibility of venue staff and other local techs to double check the information provided to them. If you work in this capacity, be sure to always “advance” the show by contacting artist/tour representatives.

During the advancing process, double check the docs that were previously provided to you by emailing them to your tour contact. This simple confirmation of accuracy can save many headaches.

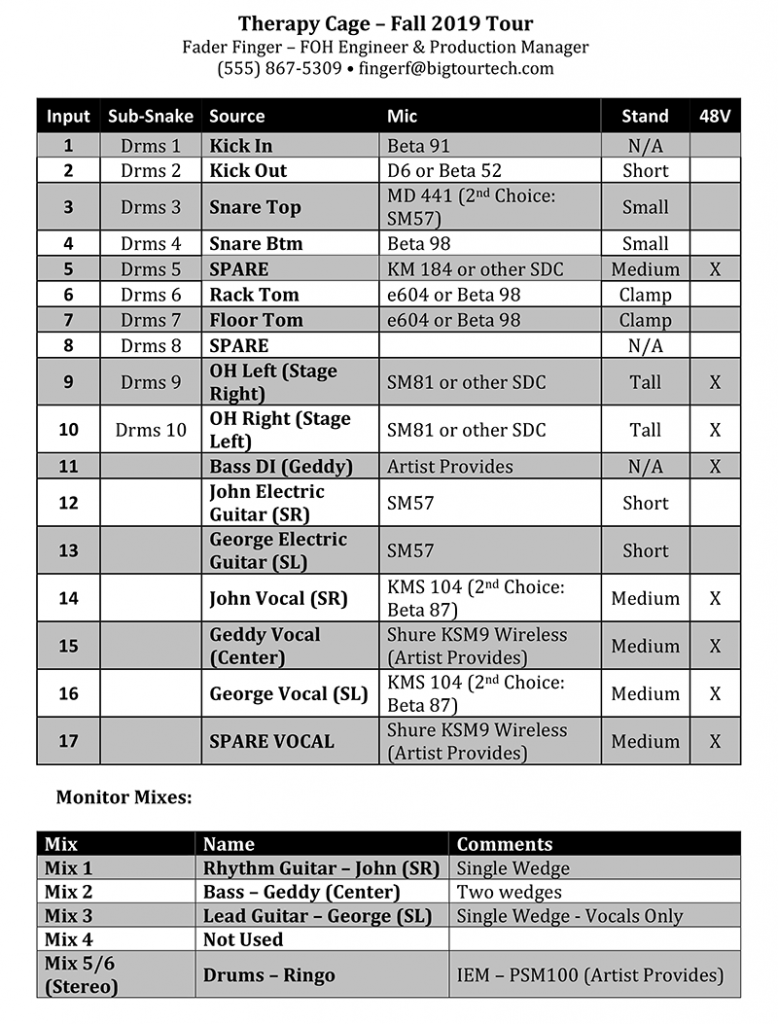

Getting Started: Input Lists

Inputs lists are easy to create. The most basic list informs the reader which sound sources require reinforcement. Simple input lists, such as those used by small town bands, may not even specify the types of mics to be used. More complicated versions are usually drawn up by an artist’s FOH engineer, and are in a particular order, require specific microphones, and offer other information such as mic stand type, sub snake patching, and console outboard requirements.

As mentioned earlier, always remember your audience when making production documents. Anything that can be done to make an input list easier to read will lessen the probability of wiring and other mistakes. An improvement to the traditional text-based input list is to build the document around a table. Tables allow grid lines to be present that make it easier for the reader to see information associated with a specific input.

Taking this a step forward, I recommend shading every other line in the table. This further assists the technician in reading the document. Figure 1 offers a sample input list, demonstrating shading and other suggestions.

Opinions vary greatly regarding mic selection and technique. I won’t tackle these topics here but will voice my opinion regarding the order of sources. The most common approach is to start an input list with the kick drum on input 1 and move upwards through the drums, bass, guitars and keys, and finish off with the vocals on the highest numbered inputs. I call this the “K•S•H” method, after the tradition of the first three console inputs being kick, snare, and high hat.

Ironically, back in the days of large-format analog consoles, this method didn’t always work, as important elements such as the kick and vocals, could end up on the extreme left or right sides of a big mixing console, making fader riding difficult. For this reason, some engineers rearranged their input lists to put lesser used inputs (cowbell) on channel one, and more important sources (lead vocal) near the center of the desk (channel 16).

While I appreciate creative and problem-solving workflows, I stick to the standard kick-on-input-one approach. Except in the world of major tours, most shows rely on local crews to patch the stage – asking these techs to patch in a strange manner (such as patching the drums in reverse order) is just asking for trouble.

Another important technique is to build input lists with fader banks in mind. Modern digital consoles seem to be shrinking, with 12 or 16 input faders increasingly common. To see more inputs, the engineer must switch between banks/layers of faders.

When creating a list, arrange sources to avoid like-elements spilling across banks. It’s annoying when two drum overhead mics fall on different layers, or a pair of keyboard direct inputs (DIs) must split across banks. Related, it’s best to make sure paired inputs start on odd-numbered channels. While many modern desks have no issues with ganging stereo pairs across even-odd channels, many older consoles only allow odd-even (e.g., 15-16).

Why does this matter? Grouping stereo inputs into a pair allows EQ and other settings to be easily shared. When EQing the overheads, the engineer need only adjust one side, and the other channel automatically matches.

There’s More

Interrelated is the age-old debate between drummer’s perspective and audience perspective. For those unaware of this dispute, the question at hand is on whose left (stage left or audience left) does the left overhead sit? Whatever your opinion, clearly labeling input lists so the stage crew is informed of your preference. If they don’t know, the techs will either cable it backwards (Murphy’s Law) or pester you during setup for an answer.

Building spare, unused inputs into the list is also advisable. Things always change, such as an additional guitar being added, or a snake line found to be broken. Placing an empty channel here or there on the list grants flexibility.