(This article co-authored by Jenny Bartlett.)

It’s a joy to hear old recordings of a favorite musician remastered on CD. Especially when the remastering is done so well that you can enjoy the music more than ever.

What’s more, a great remastering job clearly reveals the recording techniques used in the past.

There’s a lot to be learned about recording by studying how they did it so well, decades ago.

A stellar example is the four-CD Dave Brubeck reissue, Time Signatures—A Career Retrospective (Columbia/Legacy C4K 52945), produced by Russell Gloyd and Amy Herot.

It’s astounding how good some of those 30-year-old tapes sound!

The mix is just right. Cymbals are bright and crisp; acoustic bass sounds full; piano and sax are warm rather than thin. And there’s very little tape hiss.

The mastering job was ably handled by Mark Wilder, a recording engineer with Sony Music Studios (formerly Columbia Records). Since the 1970s, he’s worked at Vanguard Records, Polygram, and finally Sony.

Bruce Bartlett: What was your philosophy in remastering the Brubeck tapes: to transfer them as is, or to clean them up?

Mark Wilder: In making the Brubeck compilation, we wanted the CDs to remain true to the original master tapes. Around 1984 to 1987, however, many CDs were remastered with a high-frequency rolloff (treble cut) to reduce tape hiss.

That was the philosophy of the time: to make remastered CDs hiss-free. Unfortunately, it was a destructive process.

Dave Brubeck complained about the sound of his early remastered CDs. Fortunately, we’ve learned a lot about remastering since then. I wanted to give him better treatment than that; I wanted to do it right. Our current philosophy is to adhere to what was on the originals. We don’t add equalization or reverb.

Sony’s new 20-bit A/D system helped to ensure a clean transfer from the original tapes to CD. It did the 20-to-16 bit transfer very well. Another current 20-bit Brubeck reissue is the Master Sound CD of Time Out. It’s so clear, you can hear bad edits onTake Five.

Bartlett: How does the sound of those early recordings compare with jazz recordings today?

Wilder: It’s amazing how well-recorded the group was back then. The sound is so three-dimensional, bigger than life.

Yet it’s amazing how little the engineers did to get that sound. They just put one mic a few feet from each instrument, and mixed live to 3-track—for left, center, and right. Then they edited the tape and mixed down to 2-track.

The old stuff sounds better than what we’re doing now. We’ve been going in the wrong direction sound-wise for many years. The layout of the stereo stage was more realistic then, too. Drums were on the left, piano on the right, sax and bass in the middle.

It’s easy to hear what each musician was playing because they were separated spatially. These days, you hear each instrument in stereo, on top of each other. The drums spread all the way between the speakers, and so does the piano.

In one Brubeck recording (Castilian Drums, not on this set), the stereo perspective changes radically within the recording. It starts with drums hard left and piano hard right. But when the drum solo starts, there’s an edit and suddenly you hear the drum set spread out in stereo.

At the end of the solo, you’re back to drums left and piano right. These effects are on Brubeck’s albums Countdown (Columbia CS 8575) and Time Further Out (Columbia CS 8490), .

Bartlett: How was the Quartet miked?

Wilder: Columbia was heavy into Neumann M49 and AKG C12 mics back then. Both are large tube-type condenser mics.

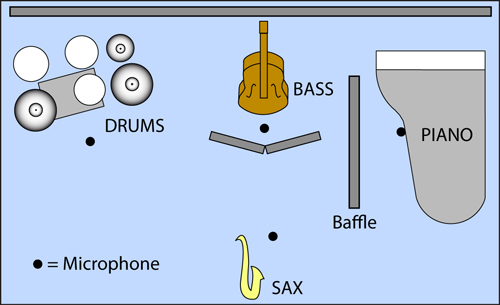

On the Brubeck groups, the engineers used one mic per instrument, and each mic was at a very respectful distance, about 1 1/2 to 3 feet away (Figure 1)…

You still hear all the air off the sax reed, and still hear all the tone. They got the placement quickly. Distant miking like this sounds great; I think we overdo close miking.

Bartlett: Some excellent photos of the studio layout and mic placement are in the liner notes of the CDs Time Out (Columbia Legacy CK 65122) and Jazz Impressions of Japan (Columbia Legacy CK 65726), and on the LP The Riddle (Columbia CL 1454).

Studio layout: Drum set on the left, bass a few feet away in the center, piano a few feet away on the right with the open lid on the long stick facing toward the other players. Sax faced the bass player a few feet away. The bass and piano were baffled. Baffles were placed behind the group as well.

Miking: Drum set—C12 about 5 feet up and 1.5 feet in front of the set, angled down toward the snare drum. Upright bass—U 47 about 1 foot from the bridge. Sax—M 49 up fairly high about 1 to 1.5 feet away. Piano—M 49 looking at the strings, about even with the curved edge of the piano, halfway between the soundboard and the lid. (This tends to emphasize frequencies around 500 Hz).