From the February 1984 issue of the late, great Recording Engineer/Producer (RE/P) magazine, Dave Brody shares some hard-earned secrets of success for surviving studio drama…

Okay, so you know all about the system gain structure, the recorders, and every toy in the outboard rack.

You’ve got the console layout under your fingers, and can play it in your sleep.

Using your extensive musical background, you make edits so smooth and tight that they all swear the chart was written that way … and you’re intimate buddies with every micro- phone in the world.

In short, you’ve got your technical chops up to an unbelievable level, Congratulations, Kimosabe, you’ve won half the battle.

I welcome you now to the dark realm of personalities and egos wherein intellect, rationality, and the stuff you learned in Engineer School are but “expression modules,” totally dependent on the patching of stronger and deeper forces for their meaning flow. It’s an emotional land where what you say is not as important as how you say it; an “unfair” universe in which the way your client perceives you is of vastly greater value than your technical qualifications.

Your most powerful tool in dealing with these matters can quiet things better than any kind of noise reduction, even out heavily transient outbursts less noticably than any compressor, and remove unpleasant feedback peaks more precisely than any filter set. It adapts itself to both balanced and unbalanced situations, but it’s tough to get a handle on – and no two engineers use it the same way.

Let’s call it the Tact Factor.

No matter what anyone tells you, only you can develop your own rap. Only you can discover and work out the rough spots in your professional personality. And only you know the particulars of your projects. But sometimes it’s helpful to look at situations in abstract; “at arm’s length,” for the sake of perspective.

Those differing with the views expressed herein are invited to write their own article. You see, life is plenty rough out here on the Cultural Frontier. Some of the Artistic lnjuns is “friendly,” but some of ‘em get a might ticked-off when you steal their Creative Hunting Grounds … and there’s no shortage of Entertainment-Industry-Outlaws. So let’s get our Tact-tactics together, podner; there’s a whole passle o’ problems to deal with.

Who’s The Boss Around Here?

Right from the git-go, we’re faced with the `How Much Creative Input Should I Express ?” question.

We all crave the ideal situation: Being given complete freedom to do the tracks any way we want. The recording game is no longer a question of getting the “best” (i.e., cleanest) sound from studio to disk (or soundtrack), but one of getting the most “appropriate” sound for the project. You must determine (a.s.a.p.!) who makes the final decision as to what that most appropriate sound is.

Yeah, it’s supposed to be the producer but, as we all know, there are producers and then there are producers (Definition: Producer – the one most likely to ask, “How many tracks we got left ?”) Engineers go for the Best Possible Track; the strongest artistic performance recorded with the most appropriate sound.

Things are not always what they seem. The guy who’s been introduced to you as the producer may not be the dominant person. Nor is the individual who talks the loudest (or longest). And it’s not necessarily the money person. It might be the quiet lady sitting in the corner. In just about every human situation there’s a Boss.

Gauging the boss’s pleasure (or displeasure) with what’s going down is the best indicator of how those involved will regard the final product and your performance. Learning who the Boss is can be the major part of psyching out the social scheme of things.

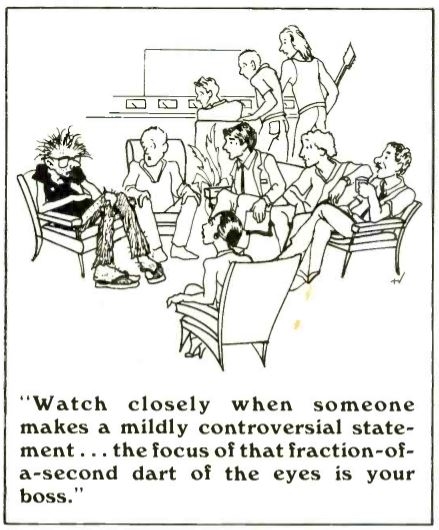

There’s a behavioral game that we humans play. I call it: “Everyone look up to the Boss” (aka: “The eyes have it … “). Watch real closely when someone makes a mildly controversial statement or raises a question of direction. Most of the people in the room will give a quick glance at one particular person. The focus of that fraction-of-a-second dart of the eyes is your Boss. (Caution: The person who first answers the question, or speaks to the statement, is likely to be the one who is most threatened by it, and may not be the Boss. And if not, the speaker will check out what he or she is saying with the same glance at the Boss.)

“And some have greatness thrust upon them.” Here’s the real Freaker. You may find that when a controversy comes up, they all look at you! An engineer behind his or her console can be a pretty impressive figure (that, as we all secretly know, is why we became engineers in the first place).

You then have three options:

1. You can defer the privilege of answer to the one you figure to be the Boss and, without seeming disinterested, suggest to them that you don’t want to get in the way of their creativity.

2. You can give an “information only” answer; i.e., play the roll of technician/ recordist.

3. If you have high personal hopes for the future of the project, and are willing to take the gamble of your own ambition, you can express a creative opinion. If you’re employed by the studio, you’d better make damn sure that everybody knows its your personal opinion. Humble is safest.