Digital Reverb

The fourth type of artificial reverb, digital, also has a wide range of cost and quality. They vary from devices with interesting and useful effects but marginal reverb, to all the bells and whistles included in very high quality reverberation devices. To produce the latter requires an extremely high speed computer as part of the circuitry, not exactly an off-the-shelf processor or inexpensive item.

The buyer of any reverb unit should listen to it with as many different types of music as possible, preferably some short brass passages so that the decay characteristics can be heard in the open. Sustained music like strings will show if there is coloration which will cause “clutter,” and some short percussive sounds will expose periodicity.

For the reader who would like to go into more detail on these and other characters tics of artificial reverb devices, the remainder of this article will be devoted to how each of the four types of reverb performs with regard to the various characteristics.

Although natural reverb will be factored into this discussion it will become increasingly obvious that reality is not necessarily an achievable or even, at this time, a desirable goal for most popular music.

Perception Of Reverberation

Purists may tend to scoff at this, but the truth is that the present state of the recording art simply cannot recreate music in its existing natural acoustic field, so it is left to that artist, the recording engineer, using close mike techniques and adding reverb, to recreate it as best he can.

If he tries to capture natural acoustics in a recording he often instead gets that dreaded “off mike” sound, caused by the comb filter effects of direct and early reflected sound; yet this problem does not occur with two good ears at the same location as the mike (not to be confused with the loss of intelligibility which occurs when the ears are presented with a low ratio of direct to reflected sound).

Next time you go to a live concert notice how you are not aware of any reverberation — yet if you listen to a recording of that music made at that same concert, you will be very conscious of it. Neither stereo nor quadraphonic has brought us the solution to this problem. Recent research in vision has brought to light that the brain has a processing channel strictly for depth perception.

Because of two slightly different images seen by each eye, the stereoptician can recreate visual depth, but the closest we can come for audio to simulating a depth perception channel in the brain is “binaural sound” or earphone reproduction of a dummy head recording.

Some experimental work is being done in “holographic stereo” by cross feeding a specialty processed signal to cancel information from the right speaker which is diffracted into the left ear and vice- versa.

Until the scientific community gets away from its present preoccupation with “direction sense” hearing theory and grapples with depth perception, it will remain for recording engineers and their producers to stimulate that depth perception channel with any means at their disposal.

Comparison

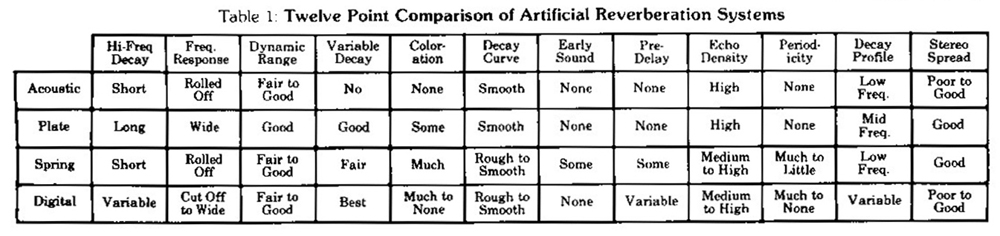

Table 1 (below) shows how the four artificial reverb devices perform with regard to a dozen important characteristics common to all of them.

The first, high frequency decay is important because, as explained previously, a long (2 seconds or more) high frequency decay can be a useful effect in pop music. The acoustic chamber and spring reverb are about the same as natural reverb.

Most of the digital units are variable, a very useful feature if the control allows the 8 to 10 kHz range to be varied without overcompensating the 4 to 5 kHz range. Most plates are outstanding in regard to high frequency decay time, but the thickness is a critical factor and unless special methods are used to obtain a high thermal conductivity, a small, thin plate will have its high frequencies damped by atmospheric pressure more than a thicker plate.

Frequency response is a good way to predict the usefulness of a reverb unit for your application. Figure 3 shows the warble tone response of each of the four types. The plate has the widest frequency response and the digital has the flattest.

Although the acoustic and the spring appear to be inferior, this type of curve may be preferable for large orchestra recording. Of course, equalization may be used to alter, to a limited extent, these curves.

Dynamic range is the difference, expressed in decibels between the overload point and the noise floor. The overload point usually begins in the higher frequencies and is mostly a problem associated with electronic or mechanical reverb systems. Plates and springs usually employ some high frequency pre emphasis thus reducing the power handling of the driver amp at these frequencies. Digital involves a similar design trade off so if you’re big on lots of echo on castinets, you might hear some distortion.

Most digital reverb devices offer the widest selection of decay times, from more than a minute to less than half a second, while plates can be varied from one to five seconds. Springs are not normally variable, although some of the higher cost units have a 2 to 4.5 second variation. Most of the variation in decay time with the last two types will be more in the middle and low frequencies rather than the high frequencies. Acoustic chambers are not generally variable.

All rooms exhibit coloration or resonances due to cancellation or addition as a periodic signal and its reflections meet in space.

Editor’s Note: This is a series of articles from Recording Engineer/Producer (RE/P) magazine, which began publishing in 1970 under the direction of Publisher/Editor Martin Gallay. After a great run, RE/P ceased publishing in the early 1990s, yet its content is still much revered in the professional audio community. RE/P also published the first issues of Live Sound International magazine as a quarterly supplement, beginning in the late 1980s, and LSI has grown to a monthly publication that continues to thrive to this day.

Our sincere thanks to Mark Gander of JBL Professional for his considerable support on this archive project.