Every December for the last 13 years, Dave and Patty Tyler, owners of Tylerland Recording Studios in Rome, NY have gathered at a local bar with about a hundred of their closest friends and hosted a night of music featuring their own band, TYLER, joined by numerous other local acts.

I’ve handled audio and production management for this event for the last few years, with all the challenges that come with bringing big shows into small venues. Thanks to the cornucopia of “blessings” that was 2020, the 14th Annual Tylerland Jam could not go forward as per tradition, but Dave and Patty asked what would be possible in terms of moving the event to an online streaming format.

If you’re hoping for some revolutionary streaming tips, this article offers nothing of the sort. Sorry. On the contrary, I quickly came to the realization that I had no idea what I was doing. More accurately, I understood the general approach and what needed to be done to pull off a livestream, but I had very little practical experience to draw upon, and there be the dragons.

Additional challenges: an extremely limited production budget and only a few days between the filming and intended air date. From an equipment standpoint we were limited to “whatever we had lying around.” Could we “MacGyver” a streaming rig together and still have the final product ready in time?

Establishing The Process

Since renting a venue or studio space was out of the question, we found some suitably large unused office space in the building out of which the Tylers run their engineering business. At 18 feet wide and about 40 feet deep, it was “just big enough” to get the band set up along with room for lights and cameras. It was a stroke of luck that my longtime production partner, Bill Di Paolo, stores his equipment for his production company, Entertainment Services NY, in an adjoining building, which meant that his gear was just a short push and an elevator ride away.

As preproduction talks continued, we settled on pre-recording each artist’s set and then editing everything together to create a final product that could offer a higher production value, tighter cueing, no need to wait for changeovers, and of course the ability for a “do over” if a mistake were made.

We started with the foundational elements: a pair of lifts, a truss span and some pipe and drape provided a simple but effective framing for a “rock show” look. The camera approach required some thought. We had at our disposal a pair of mounted television displays and a pair of 1080i DV cameras, usually used for IMAG and archival purposes at corporate events, and the band owned a GoPro camera that we could use for a third angle.

I had wanted to record each camera independently and then edit the entire show together, but capturing in all the footage off the DV tapes added a time element that might not have been feasible. The alternative would been to switch between all three cameras live and just capture the switcher output, which is risky in a different way, and we didn’t to end up “stuck” with a bad camera cut or awkward transition.

We settled on a compromise approach: a “2.5 angle” shoot. We would switch between the two DV cameras live – one as a wide shot, one as a manually operated closeup camera, record the output of a switcher direct to computer via an Elgato capture box, and also record the GoPro directly as a separate feed. The editing process would then consist of cutting between the two video streams, a good combination of flexibility and turnaround time.

Routing The Elements

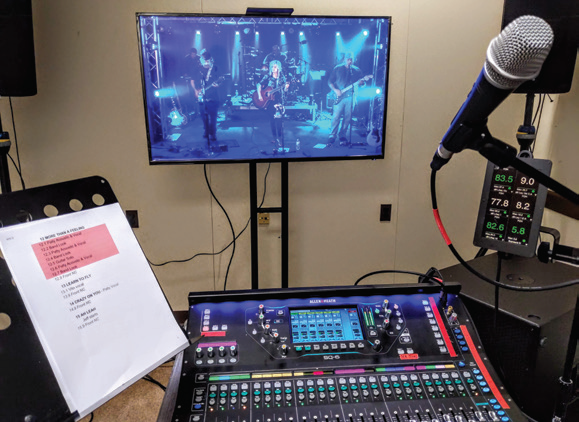

The main elements of the audio system were in place: the band owns an Allen & Heath SQ-6 console, used in conjunction with an AR2412 stage box. I set up a “broadcast” room in an adjoining office where I could view the output of the video switcher on a TV and mix the show. Since I was familiar with the TYLER set list and had a fairly intricate showfile, I would mix the performance live to 2-mix, saving me many hours of rebuilding the mix in a DAW.

For the three other artists on the bill, I would record their performances to multi-track and send the files off to my friend and fellow mix engineer David Williams, who would be able to work on those mixes while I was cutting the video together. My monitoring rig for the live mix was a pair of JBL PRX612M and an RCF SUB 8004-AS subwoofer (Figure 1). The board mix was routed to my Symetrix Prism DSP for tuning and alignment and then on to the loudspeakers.

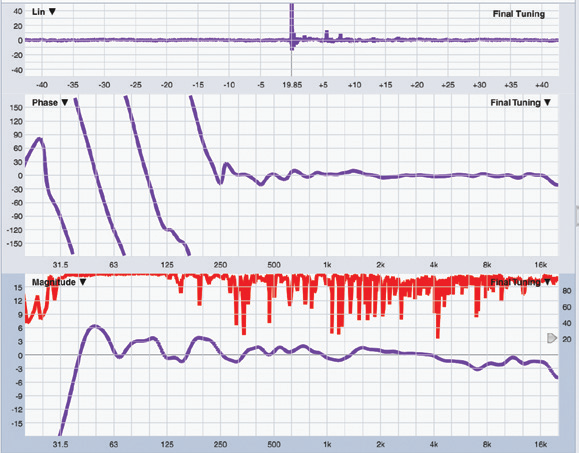

Originally, the plan to do the entire event live meant that the Prism would be playing a much larger role with console combining and brick-wall limiting, but I did decide to treat myself to a hand-rolled FIR filter (designed with Eclipse Audio’s FIR Creator application) to phase-linearize the monitoring system above 250 Hz, in addition to tuning it to the relatively neutral target curve I mix into for the TYLER shows (Figure 2). Despite the telltale signs of a small room in the low end of the spectrum, I found the TYLER board mix translated well without much fuss.

I was also looking after five stereo IEM mixes, plus additional IEM and wedge mixes as required for the other acts, and I needed to devise a foldback / shout system for the crew. (Thanks to guitar amp sims and load boxes, the TYLER stage is silent except for the drums, so anyone in the room during the performance would have a thoroughly unremarkable experience without a monitoring system.)

Actually, two talkback routes were needed: one to speak to the artists and crew together, and one to call cues for the crew without disturbing the artists. To solve this, I set up a switched talkback microphone using the SQ-6’s onboard talkback functionality to allow me to talk into the artist IEMs when the TALK button on the console was pressed.

I also routed the board mix to a matrix and injected the talk mic preamp directly into that matrix, which was routed to a previously retired headphone distribution amp for the crew headphones. That way, any time I switched my Talk mic on, I could be heard by Bill at the lighting console, Nate Clark at the video switcher, and Ryan Goodwin operating the video camera. Pressing the TALK button on the console surface would additionally route the talk to the artist monitors.

Reflecting On The Result

All things considered, the two days of filming and subsequent post-production went well. The cameras required some fiddling with contrast, saturation and exposure to enable the “rock show” lighting to translate well. Getting a 10-year-old interlaced DV camera to look reasonably similar to a modern GoPro, especially with limited video knowledge, was a bit of a challenge, and I’d like to implement a more full-featured comm and talkback system next time.

But overall, given the constraints we turned out a fun experience for over a thousand viewers on New Year’s Eve, and were able to bring some much-needed attention to charities doing important work during an important time.