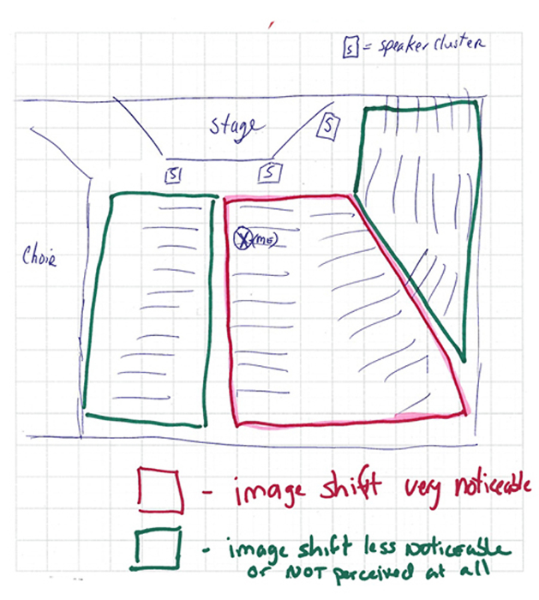

The public image of a church is important, but there’s another kind of image – of the sonic variety – that’s also significant. During a recent worship service, I got to thinking about image in terms of where sounds are coming from on a stage and where I actually perceive them as coming.

Specifically in this case, there was a choir singing, and it was located far left. In fact, I had to turn my head almost 90 degrees from the main stage to see the choir. The reinforcement for the choir was coming from loudspeakers flown centrally above the stage, and from where I was sitting, the reinforced sound was louder than the acoustical sound of the choir. Thus my attention was drawn to the stage, which was void of any performing musicians, rather than the choir.

My “sight brain” was telling me the choir was far left, but my “hearing brain” was forcing my attention toward the stage. This is an imaging issue, and it was driving me nuts. Now, if I’d been located closer to the choir, where the acoustic energy of the choir would likely be louder than the reinforced sound, I would have “localized” on the choir and likely would have interpreted the reinforced sound as an “effect” – a quasi-stereo image.

Or if I had been located more toward the right side of the sanctuary, the reinforced sound would have seemed more “in line” with the location of the choir. Even though the reinforced sound would still be louder, it would make sense in the sight-sound-brain equation, because the acoustical image would be more in direct line with the choir.

Side note: the room was a small enough that the distance from the choir to the loudspeaker covering the right side of the room was not great enough to cause the listener to perceive much, if any, delay between the acoustical and reinforced sound.

The next time I visit this church, I’m either going to move to my left (closer to the choir) or to my right, far enough over to align the reinforced sound with the acoustical image. And, to improve this situation, my suggestion to the church is to add a secondary loudspeaker(s) that hangs above the choir that will help clear up the imaging problems. The acoustic and amplified sound would be coming from the same direction.

On The Other Hand…

Fast forward a couple of weeks. I attended a hymn sing/brass concert in a different worship center. During one song, five of the brass players went up to the balcony and played from there, echoing the players on the stage.

It sounded incredible! At times it had the feel of a question and answer session, where the stage musicians would play, answered by the musicians in the balcony. Other times they both played together, and if felt as if I was in the middle of an entire brass section. This was excellent imaging.

The reason the imaging worked is because it was set up as an effect. The antiphonal response of the brass in the balcony was a purposeful image shift that enhanced the musical piece. One on my pet peeves is listening to a band playing over a left-right stereo system, and the toms on the drums are panned to give separation. But when I look at the drums, rather than the sound going from right to left – following the drummer as he runs the toms – it does the opposite. Again, imaging makes a difference.

Another thing that I like to do when I’m mixing in a stereo situation is to try to move the image of the instrument relative to where the musician is standing on the stage. If the guitar player is on the right side of the stage, I will pan the feed of the guitar slightly to the left, and so on.

Shifting Gears…

While recently discussing in-ear monitoring (IEM) with a colleague, he made a statement that struck me: “In reality, it’s the smaller church that needs in-ears much more than the larger ones.”

A couple of things came to mind. Larger churches/ministries have the funding to get IEM, and they (often, at least) have paid technical staff that can properly set it up. And larger churches also have large stages in large rooms, and stage volume is frequently not as much an issue as it is in smaller churches.

However, here are some (now rather obvious to me) reasons a small church might invest in IEM:

• Stage volume is a huge issue. In some cases, 70-plus percent of the congregation probably hears more stage volume than sound coming out of the main loudspeakers.

• Because of the stage volume, there are continual complaints about loudness and that the vocals cannot be heard over the instruments.

• Further complaints about not being able to hear the vocals.

• Many small churches have singers and instrumentalist that have never played on a big stage and are perhaps self-conscious about their abilities. IEM allows them to better hear themselves and other musicians.

• Feedback can be a constant issue because the vocal monitors always need to be turned up too hot so the singers can hear themselves.

So, how can smaller churches move into IEM? Fortunately, costs have come down in recent years. Further, an investment can be made in just a few systems, with more receivers added over time as funds become available.

I suggest starting with singers; although they’re not the loudest thing on stage, in general, their monitors tend to be loudest. So a good starting point might be purchasing one transmitter and enough receivers for all of the vocalists. Then later, purchase a second transmitter and put the band on that mix. Issues to keep in mind with IEM:

• They do take a bit to get used to, so use them first in multiple rehearsals.

• Mixing for “ears” is different than what is needed with standard floor monitors.

• Without ambient/audience mics feeding IEM, musicians will initially feel isolated and perhaps frustrated.

• Just like conventional monitors, when multiple musicians share a mix, there will be issues!

To help make the use of IEM successful, the person providing the mix (usually the house sound operator) should use a set of headphones (or earpieces) that match the ones the musicians have when setting up the monitor mix on an aux send on the console. Also, the operator should try to make sure there is an ambient microphone (or two) to feed that aux channel (and not the main mix).

I’ve found that placing a mic to capture some onstage sound as well as a mic to capture the audience/house sound usually works the best. Dialing the amount of each mic into the mix is a matter of personal taste – work with the musicians on this one.

In-ear monitoring is not a total solution to all stage monitor problems, but it’s a valuable tool that can help when deployed carefully and correctly.