Making A Way

At this point most concert loudspeaker systems were quite simple, comprised of either multiple instances of the same model of loudspeaker (often arranged in a column) or combinations of cone loudspeakers and horns (to handle the low and high frequencies, respectively). Being as any given loudspeaker has difficulty delivering a range of more than three to four octaves with clarity and low distortion, these systems could not be considered high fidelity.

What was needed was a way of splitting up the signal into multiple frequency bands that could be more efficiently handled by individual amplifiers, and then recombined in a manner that was pleasing to the ear. And the emerging PA companies were falling over themselves to accomplish just this.

In 1969, Watkins unleashed the Festival Sound System, one of the first 4-way sound systems, splitting signal into bass, lower-mid, upper-mid and high-frequency portions. A short while later (early 1970), Bob Heil was called into service to build a monstrous 4-way system for the Grateful Dead at the Fox Theatre in St. Louis. He estimated that the total audio power of this system was around 20,000 watts (despite being powered by home hi-fi amplifiers!).

Clair Brothers developed its first 4-way system by splitting the sound up into bass, mid, high and super-high bands, and in 1971 McCune Sound Service (San Francisco) employees John Meyer and Bob Cavin created a loudspeaker known as the JM-3 (named after John Meyer). This was a 3-way system that also enclosed the amplifiers and all of the integrated electronics in an external equipment rack.

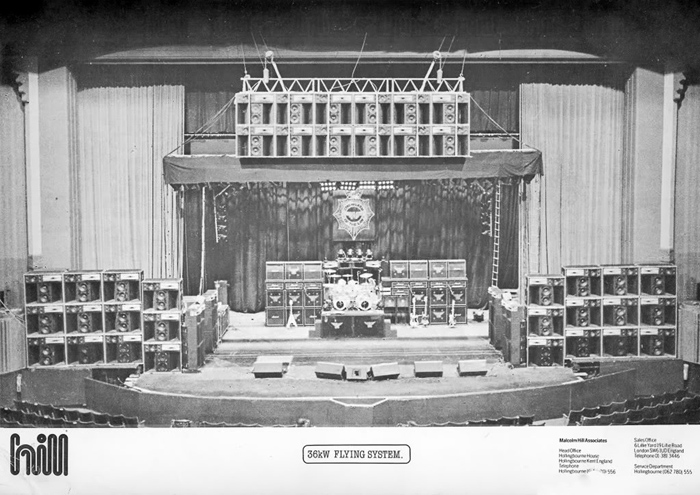

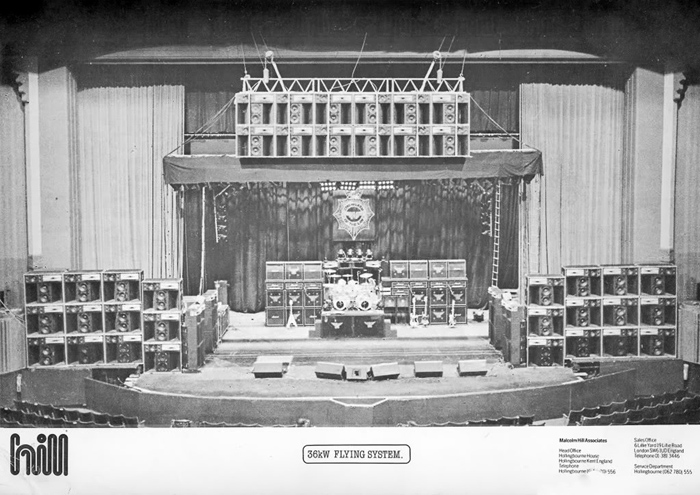

Thus at the dawn of the 1970s, we entered the golden age of the ground-stacked PA system – so called because the bass loudspeakers were placed on the ground or stage, with the mid and high loudspeakers stacked on top.

Many of the those early big PAs were based on aging loudspeaker models such as the Altec “Voice of the Theatre” Series (from the small A8 through to popular A4 and the large A1), which were designed more for use in cinemas and theatres.

Gradually PA companies such as Clair and Heil Sound shifted toward use of transducers (cone and compression drivers) developed by JBL Professional, a company with a rich heritage extending back to its origin in 1945. Notable developments include the D130 15-inch cone (introduced in 1947), which was the first commercial use of a 4-inch voice coil (a variant of which remained in production for the next 55 years), and the model 375 (introduced in 1954), the first commercially available compression driver with a 4-inch diaphragm.

Mix And Monitors

Live mixing consoles as we know them today came with a big assist from the recording side of audio. Bob Heil adapted a Langevin studio console for his fledgling large-scale PA in 1970, and he was also an early user of the Mavis console from IES in the U.K. as well as working closely with the Sunn engineering department on the first 8-channel Coliseum mixer (which was hand built).

A few years later, Ron Borthwick and Bruce Jackson, working with Clair Brothers, developed an unusual mixing console, the CBA 32, that went on to become the company’s mainstay into the 1980s. It was the first console to offer plasma bargraph meters, which displayed both average and peak sound levels, and the meters were conveniently located beside the faders. In addition, it was the first live console to incorporate parametric EQ.

Another key step was the development of more complex stage monitoring systems. Prior to this point musicians had either relied on carefully balancing their levels so they could hear everything they needed or they placed loudspeaker stacks at the side of stage which “folded back” the main mix (as those early mixers didn’t have auxiliary outputs capable of providing monitor mixes).

But the increase in the size of the PA systems meant monitors were becoming more of a necessity for the performers to not just hear and feel the performance, but also to be able to sing in tune. Pretty soon, curious wedge-shaped loudspeakers started appearing on stages, and once musicians heard them, they all wanted one (or more).

It’s interesting to note that such additions were not always welcomed by front of house engineers. For example, Pink Floyd engineer Mick Kluczynski observed that wedge monitors spread “like a virus” and he quickly found himself battling a secondary sound system, struggling for control of the main mix.

Basic Template

Loudspeaker capability developed and grew throughout the 1970s, with the 3- and 4-way ground stacked system dominating and then gradually taking to the air over the next 25 years or so. While hanging or suspended systems were developed, the basic template remained the same.

These systems are often referred to as “point source,” meaning they propagate sound equally in all directions, but that can be misleading. In reality, they only behave like a point source at lower frequencies and gradually become more directional as the frequency goes higher.

As a result, they tend to “spray” a lot of bass and lower mid range energy in all directions – against the ceiling, floor and side walls – causing delayed reflections that can muddy the sound and make it difficult to manage.

Point sources also conform closely to the inverse square law, meaning that the sound level drops by a quarter for each doubling of the distance from the source due to the fact that the expanding sphere of sound energy is spread over an increasingly larger area. This is another easily observable property as we all know that the sound is typically louder at the front, near the loudspeakers, and quieter at the back.

During this period, numerous manufacturers entered the concert market, presenting increasingly sophisticated loudspeaker systems. JBL Professional, Meyer Sound, Martin Audio, EAW and Turbosound are just some of the names, with the growing number of local and regional sound companies now having the opportunity to purchase “off the shelf” packages instead of designing and building their own loudspeakers.

EAW in particular enjoyed huge success with the KF850, a 3-way “arrayable” loudspeaker designed by Kenton Forsythe – for several years it was tough to find an equipment rider that didn’t include the KF850. Meyer Sound lead the way in developing self-powered live systems, with amplification and electronics matched to the specific loudspeaker parameters and physically housed in the same enclosure.

Line ‘Em Up

Then in 1993, Christian Heil and his team at a company based in France named L-Acoustics launched the “modern” line array era with the introduction of the V-DOSC system. I say modern because the principals behind the line array have been known and used (in a limited sense) for quite some time.

Harry Olson first published his findings on the subject in 1957, and the benefits of column loudspeakers (where vertically aligned drivers in a single enclosure produce mid-range output in a wide horizontal and narrow vertical pattern) had been utilized in the Shure Vocal Master PA and Marshall columns that were available in the 1960s and beyond.

L-Acoustics refined the science and exploited the constructive interference caused by closely aligned loudspeakers to push sound energy further, and with a more even frequency response. The company’s “cylindrical wave generator” also focused output more in the horizontal plane and wasted less energy in the vertical plane, resulting in a more even distribution of sound throughout the space.

Line arrays are very much a product of the computer age, with precise modeling and precision deployment key to getting the required result. However, it’s important to note that line arrays are not the ultimate sound system; there are still many situations where a traditional flown or ground stacked approach is better suited.

The driving force behind every pioneer highlighted in this fascinating journey has always been the desire to provide a pleasing experience for the audience. As the technology advances, we as audio professionals are more able to place the sound precisely where it’s needed to provide the visceral experience that only a live performance can provide.

But it’s important to remember that the PA is merely the conduit for the performance. If you were able to directly compare the concert experience of someone in 1964 with someone in 2014, chances are they would express the same degree of joy and excitement at what they had witnessed, despite the obvious gulf in fidelity. Because at the end of the day, it’s all about the music.