When it comes to discussing the fine art of mixing music, I tend to approach the subject with some trepidation. After all, compared to many of the topics I’ve written about, this one is rife with subjectivity — one person’s idea of a great sounding mix may be another’s sonic nightmare. And what works for one genre of music will be decidedly wrong for another.

But all those variables aside, there are at least a few general theories, tips, and tricks that apply to most mix projects. So while the idea here is not to give a step-by-step tutorial on 2-track mixing, hopefully we can cover at least a few concepts that are useful for everyone.

The Concept

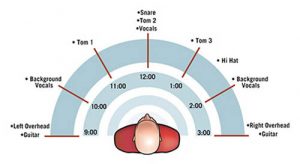

At its most basic, mixing in stereo means mixing for the human brain and physiology. “True” stereo mixing involves creating a sonic picture that replicates what our two ears hear — and our brains decode — in the real world.

For example, the brain localizes a sound by measuring the time and tonal differences between the sound arriving at one ear and the other. In a perfect world, a true stereo mix would create a sound that’s as close as possible to an organic, live performance.

But in the real world, much of the process of creating a stereo mix is far from organic or natural. Part of this is due to practical considerations. In a live performance, the acoustics of the venue itself play a prominent role in blending the sound sources and masking the localization of any particular instrument. In the studio, tracks tend to be recorded separately, in a relatively dry setting, enabling us to control their perceived ambience with the aid of technology.

In actual practice, modern stereo mixing has less to do with replicating real world conditions than with creating a good sounding balance between the various musical elements in a recording. It’s probably safe to say that most modern recordings bear only a passing resemblance to the sound of a band playing live in front of the listener.

What Makes A Good Mix?

As stated earlier, the definition of a good sounding mix is largely in the ears of the listener. But most engineers will agree that a good mix should contain a few common characteristics:

Clarity: Each sound in the mix should be clean and clear — no muddiness or blurring of the sounds or the stereo image, no excess noise or other anomalies.

Separation: Each instrument and part should be easily discernable. Sure, there’s nothing wrong with a “wall of sound” if that’s what you’re after, but even within those big, lush guitars, a great mix will be crisp and well-defined enough for the listener to pick out individual sounds.

Balance: The mix should offer a good balance of frequencies. A mix that’s too bottom heavy or too shrill will be unpleasant and exhausting to listen to. The mix should also be balanced between left and right channels.

Space: As with balance, this applies on many levels. The music itself should have space – places between the notes where things breathe and dynamics develop. Of course, this will vary depending on the genre of music. There should also be an element of natural ambience to each instrument, and the ambience for these different instruments should blend well with each other.

Needless to say, these characteristics alone do not make for a perfect mix, but a mix that lacks any one of them will very likely end up being at least a little bit problematic.