This article began as a discussion of some of the techniques used to provide streaming mixes for a large series of “drive-in” concerts in August of 2020. Since then, the audio production world has seen more and more streaming events take place.

Many mixers who are used to mixing on large PA systems have now had to adapt to a different way of thinking and figure out how to provide streaming audio. What are LUFS? What is loudness? How do you control all this without sounding thin and “squashed”? These are skills that broadcast music mixers have worked with for years prior to the pandemic.

This article presents some of the techniques to help front-of-house mixers change perspective and hopefully upgrade their streaming mix activities.

Introduction

With the onset of the pandemic, the live production industry shut down literally overnight. Since then, we’ve all learned that the industry, one that depends on putting large groups of people together in rooms and outdoor fields, would not return to the status quo for a significant period of time.

Necessity, however, breeds invention and the concept of a drive-in concert has spread quickly. As a means to quickly get back to “something,” the industry adopted these shows all over North America. The shows consist of artists performing on a normal performance stage; however, the ubiquitous PA system is usually either used at lower volume or simply not used at all. Instead, the performance is “broadcast” over low-power FM systems to the car radios of the on-site attendees.

With the growth of these shows during the summer and the huge increase of “live-to-web” streaming performances in general, more and more FOH mixers find themselves in a spot that they may not be used to – being a broadcast music mixer.

Different Perspectives, Different Tools

Mixing for broadcast isn’t really that different than mixing with a PA, right? Well… not quite. There are indeed differences due to change of perspective.

FOH mixers generally have practical implications to contend with – the size of the PA, how it’s flown (or not), coverage, tuning, regional sound level restrictions, etc. Some of these issues are dealt with when the PA is designed while others are handled as the mix is built and continually tweaked during sound check and the show.

Since the environment that the system resides in becomes part of its response, that environment, whether it be outdoors or a room, influences the mix. As a result, the mixer may not add all elements coming from stage to the PA mix and definitely not at the same level as would be for a broadcast. In addition, the audience, being present in the space, is able to physically experience the performance, which allows them to buy into what the mixer is doing to match the sound to the experience.

In a broadcast mix, the perspective is a little different. As with an FOH mix, broadcast music mixers have to decide how and what elements of the onstage instrumentation are critical for the mix. They also, however, have to ensure the mix satisfies the visuals that are presented to the audience, in which case the music mixer needs to handle one strange aspect: the sound needs to “look” right and it needs to satisfy the audience’s expectations of what they would hear if they were in the space in which the performance is occurring.

This means that those mixing for streaming and drive-in shows have to be aware of how the mix works in a context that FOH mixers normally don’t need to concern themselves with. Panning of instruments in the performance, for example, becomes more important as the audio needs to be in full agreement with the elements seen on screen.

As well, mixers also must “manufacture spaces.” For example, in a standard stage show, It’s common for mixers to add various reverb and delay effects to vocals during the song and remove them during stage banter in between. On a stream, however, this feels odd or unnatural. The performer is in the same room as during the song – how come their voice doesn’t sound like it? When the voice goes from saturated reverb to fully dry, the effect becomes apparent and subsequently distracting.

A little judicious reverb (obviously way less than that used in the song!) helps preserve the “space” that the viewer is seeing the performer in. The addition of a little “sauce” helps ensure the sound matches the look. Please note the usage of the word “judicious” – I’m not in the least suggesting that each element swim in manufactured reverberation; however, it’s important that this consideration be given different consideration from a broadcast perspective.

Loud-Loudy-Loudness!

Another angle that broadcast music mixers may be more used to than FOH mixers is the concept of loudness and loudness metering. This is a big topic that needs some exploration before we look at how it can improve drive-in and streaming mixes.

Typically, most mixers are accustomed to using the standard meters available on their console. Whether they’re the LED-segment PPM (peak program-meters) on digital desks or analog VI (volume indicator meters, often improperly referred to as a “VU” meter), we’re used to looking at these meters to gauge what our audio is doing.

In broadcast, due to regulations designed to help ensure commercials are no louder than the program components they accompany, music mixers routinely use loudness metering. This brings a completely different perspective than that used with standard PPM or VI metering.

What’s In A Meter?

What information does a loudness meter provide that a PPM or VI doesn’t? Both VI and PPM are essentially calibrated voltmeters. They measure the electronic level of the signal with various different integration times to affect the way the meter ballistics respond to signal peaks.

Loudness, however, describes subjective human perception of a sound. You can have two songs that meter the same on a VI meter but have dramatically different perceived loudness. We’ve all experienced this when watching TV back in the day and being startled when the commercial break comes in screaming loud compared to the relative level of the program we were watching.

In fact, this is why broadcast music mixers have experience with loudness. With the 2012 introduction of the Commercial Advertisement Loudness Mitigation Act (a.k.a., the CALM Act) in the U.S. and the Broadcasting Regulatory Policy CRTC2011-584 issued by the CRTC in Canada, no commercial content is supposed be louder in than the program material it accompanies. This means that broadcast materials and commercials must not exceed a specific loudness to avoid the jumping levels issue.

Loudness is so important to streaming that all streaming services such as Spotify, Apple Music, YouTube, and Facebook have implemented requirements. Read that this way: If you don’t pay attention to loudness, they will do it for you. As a mixer, you do not want to do that!

99 LUFS Balloons… Or Is It LKFS Balloons?

In broadcast environments like TV, the loudness limits are -24 LUFS +/- 2 LU. LUFS stands for “Loudness Unit Full Scale” while an “LU” is a “Loudness Unit.” Many may have also heard of “LKFS,” which stands for “Loudness, K-Weighted, Full Scale.” But what are they and why are they important to this discussion?

These two quantities essentially refer to the same idea: that perceived loudness can be approximately quantified measured based on open standards (ITU 85.1770 to be specific), but they’re essentially the same thing. In addition to time-domain signal integration, loudness meters apply frequency-domain weighting (a combination of a low shelf and a high pass) to attempt to approximate the tonal perception of the human hearing mechanism at moderate listening levels. This allows an absolute measurement so that we can all talk about loudness using the same references and terminology.

Once television got on board, it wasn’t long before these concepts were used to tame the so-called “loudness wars.” In an effort to make iTunes Radio sound consistent, Apple started adding the “soundcheck” feature in October 2013 to help ensure that songs would be turned down by an algorithm if they were submitted louder than the allowable limit. Now all the streaming services include some form of loudness normalization, for example:

Apple Music: -16 LUFS

YouTube: -13 LUFS

Tidal: -14 LUFS

Spotify: -14 LUFS

Why are there such differences between the TV broadcast levels (-24 LUFS) versus streaming levels? Early on, streaming services did use the TV loudness levels but identified multiple issues. First, streaming devices tend to be used in environments where there’s significant ambient noise, such as on a subway or walking down a city street. In addition, the size of these devices prevented manufacturers from adding amplifiers large enough to provide clean volume swings necessary to increase the listening level above these noise sources. To avoid these issues, louder levels were adopted for the streaming market.

Having said all that, when we come back to music mixing for streaming and drive-in concerts, a key issue becomes apparent: the mix must be loud enough to sound “right” over a stream but not so loud that the streaming service will turn it down for you. We never want the streaming services to do the work for us – their algorithms do this work in a very non-musical manner and most mixers prefer to keep this control in their hands. So how do we achieve proper loudness for our streams?

Hop On The Bus… The 2-Bus!

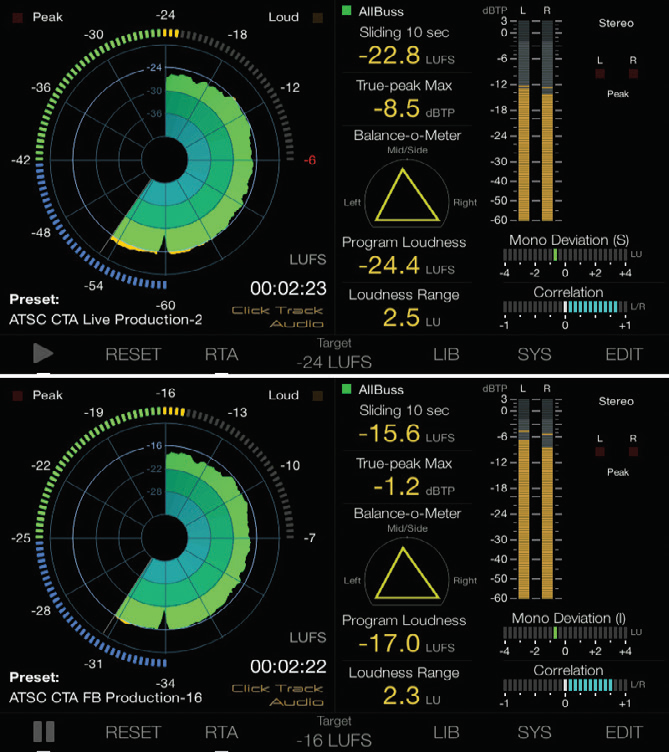

The key to making this all work is a simple bus compressor and a loudness meter. One of the more popular hardware units available is the TC Electronic Clarity M, which I use for all my broadcasts. TC Electronic has literally written the book on loudness and the practical application of loudness theory to broadcast environments. That said, there are many effective software loudness meters available, such as those provided by HOFA and Waves.

Build the broadcast mix as you would normally, of course paying attention to the basics such as proper gain staging, bus structure and compression at the various places in the mix. While doing this, also make sure there’s a fairly transparent bus compressor inserted on the final output bus. For hardware mixes, I use the tried-and-true Waves MAXXBCL, but in software, I lean toward the SSL Native Bus Compressor plugin.

As the mix evolves, one may want to ensure the vocal is “a little” forward to make sure it doesn’t get lost. Bring up the threshold to make sure it’s hitting the compressor so that the dynamic range isn’t as wide as it would normally be in a standard concert PA mix. Since many of the streaming specifications call for +/- 2 LU, you’ll notice the need to compress fairly hard to achieve this. Use the make up gain to keep the level close to the target loudness indicated on the meter.

The meter has various readouts, but using the “short term” setting, which employs a rolling average across the previous 10 seconds, provides a real good feel for how the audio is behaving across the stream. The “program loudness” or “integrated” feature does the same across the entire length of time between the user’s request to start and stop the analysis. If using a software loudness meter like the HOFA meter, ensure the scale is based on LUFS -18 LU.

The goal is a mix that sounds consistent between the high dynamic passages and the low dynamic passages. The compression used here isn’t for effect; you’re not looking for any attack/release “pumping” of the compressor. The desired effect is purely level and dynamic control. The signal should play nicely within the limits of the available dynamic range.

It takes some practice to find the “sweet spot” without over compressing while still hitting the target level, but once that spot is found, you’ll notice the mixes will sound nicely loud enough over the stream while being well behaved enough that the services aren’t affecting it – all while still being musical and compelling.

Monitor through nearfield loudspeakers as well as headphones to check what the low end is doing and how the audience will perceive the mix. As well, don’t forget to check mono compatibility! Never assume the audience will all have properly wired headphones and loudspeakers connected to their I-devices, Androids and YouTube computers.

At one recent large multi-day drive-in festival, these principles helped in providing the mixes for both streaming to the web as well as for the on-site FM broadcast. In this case, separate output buses were used to feed the FM broadcast a level of -24 LUFS while the streaming output was bumped up to -14 LUFS. The two simultaneous broadcasts were full sounding while all vocals and spoken content was clear and intelligible as one would expect.

Now that many of us are taking on new roles, the hope is that applying these techniques may help in avoiding some of the pitfalls this new paradigm presents.