I was halfway through tech rehearsal week on a college theatrical production when the lighting designer approached me and said, “What do you know about opera?”

On its face this is an interesting question for a sound engineer, as opera is traditionally performed without much, if any, reinforcement. He explained that he was involved with a production of Rossini’s Barber of Seville, staged by the Finger Lakes Opera, who for the first time was planning to stage their production outdoors. The LD knew that there would be some unforeseen challenges involved with taking a traditionally acoustic genre outdoors and felt that I’d be able to provide the necessary guidance.

The audience seating area was on a sloped hill that forms a natural amphitheater shape, with the playing area under a large clamshell-shaped tent structure, and the orchestra upstage behind the set. Although the tent structure would shield the production from the elements, it wouldn’t offer much in the way of acoustical support, which meant that anything that needed to be heard would need to be miked and reinforced.

The natural sloping bowl of the audience geometry was a prime candidate for a flown array. Coverage started about 15 feet in front of the array location, with the furthest listeners over 175 feet back, a range ratio far too large to be tackled comfortably with a ground-stacked solution. The width of the seating area meant that both sightlines and horizontal dispersion were of concern.

It was also imperative to get the loudspeaker position as far downstage as possible so as not to unnecessarily restrict the playing space out of gain-before-feedback concerns.

Delivering Coverage

After evaluating the available options from both audio rental companies involved with the show (Applied Audio & Theater Supply of Rochester, NY and Entertainment Services NY based in Rome, NY), I settled on six RCF HDL6-A elements for each of the main arrays, flown on Sumner Eventer 16 lifts with the forks inverted to gain an extra foot of trim.

More than 175 feet is a substantial throw for a small-format array product, but on the other hand, I knew the system would not be run anywhere close to its maximum capabilities as it would not be a loud program. With a few iterations of tweaking at the prediction stage, plus a bit of high-frequency tapering on site, we were able to reduce the front-to-rear level variance to within 6 dB within the vocal range while extending good intelligibility all the way to the rear, with the added benefit that the entire PA could run comfortably off a single power circuit per side – another important consideration, as audio was sharing an electrical service with video and lighting.

Beside each lift was a pair of RCF SUB-8004-AS subwoofers in cardioid configuration, providing the low frequency extension necessary for natural-sounding reproduction of cello, bass, and timpani. The cardioid preset dramatically reduced the amount of LF energy washing back onto the performance area, towards the orchestra and performer’s mics.

In addition to the main arrays and subs, we also deployed a pair of JBL AC15 compact loudspeakers as front fills to close the coverage gap between the mains for the folks sitting in the first few rows. Three more AC15s were deployed across the downstage edge of the performance area as foldback so the performers could hear the orchestra, and an additional pair mounted within the upstage set (a structure based on construction scaffolding).

Rounding out the foldback system was a pair of Galaxy Audio Hot Spot HS7 monitors so the conductor and pianist could hear the vocals.

Thirteen channels of wireless microphone systems for the singers (Shure QLX-D packs with a variety of elements from DPA, Point Source Audio, and Countryman, supplied by Cooper Sound Design) were routed to the Allen & Heath Avantis console at mix position via an Allen & Heath AR2412, with an additional AB168 located upstage behind the set for orchestra inputs, which were predominantly Shure SM81s, with a pair of Audix A127 condenser microphones on percussion elements. The A127 mics are newly released and have impressively low self-noise, so I was happy to incorporate them on this show.

Routing Around A Wrinkle

Rather than a more traditional left-right stereo mix, the show was mixed into three stereo groups (Orchestra, Vocals, and Playback) then routed to an Allen & Heath AHM-64 matrix processor that acted as the “mothership” of the system.

From there, the groups could be routed to all the different output zones as required, which allowed me and my team (assistant audio engineer Hannah Goodine and production sound intern Shannon Scally) to quickly deploy the system and simplify the operation while streamlining the amount of routing and busing that had to be done via the mixing console.

Production inputs such as “god mics” were routed directly into the AHM-64 into the foldback zones, which allowed the stage management team to make announcements at any time without having to worry about interrupting whatever programming work we were doing at the console.

Throughout the tech process, I had a series of conversations with maestro Gerard Floriano, who is the artistic director of the Finger Lakes Opera and conducted the orchestra for the show. Playing from behind the set meant that Gerry and the orchestra members could not see or hear the on-stage action as they were accustomed to.

A video camera at FOH connected to a video monitor near the conductor’s podium allowed Gerry to see what was happening on stage, while a lipstick-style conductor cam transmitting to two TV screens along the downstage edge allowed the performers on stage to follow Gerry’s conducting. (These types of video systems are common in musical theater performances, so luckily we didn’t have to reinvent the wheel.)

I routed a vocal mix to a Galaxy Audio Hot Spot near Gerry’s podium – and a second one near the keyboard player’s position – and although I did my best to make that mix as representative as possible of the vocal performance that the audience was hearing, it’s obviously quite a different monitoring situation than what one would experience standing in an orchestra pit and hearing the natural acoustic propagation from singers on stage.

Gerry and I would have a conversation after each rehearsal to make sure he was hearing everything he needed to hear and talk about how the orchestra’s playing and balance was translating through the PA out front. Since we were dealing with a genre that is not traditionally reinforced, I wanted to keep the sound as natural and open as possible, so we tried to achieve any needed dynamic or balance changes via his conducting and balancing of the orchestra, with me gently pushing and pulling the orchestra mix out front as required.

This created a much more “organic” and transparent sound than trying to “force” dynamics onto the orchestra’s performance at the console, and I’m of the firm belief that the ability to have dialogues and work together about these types of performance facets will do more for the quality of the show than any choice of microphone or processor.

Taking It In Stride

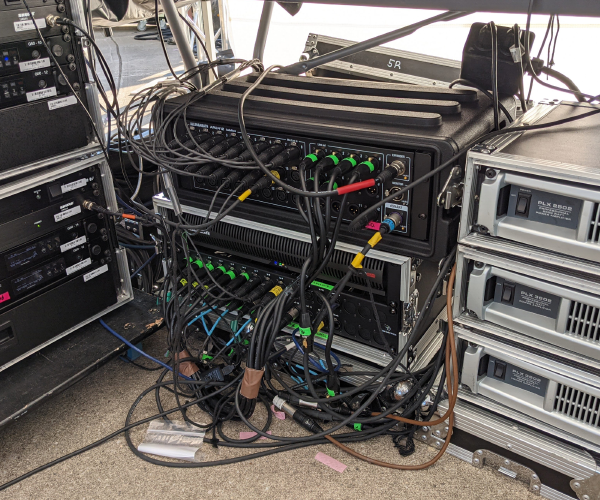

Hannah managed the deck sound position, located in a tent downstage right of the main performance space. Under the tent were the RF receivers, antenna distribution and paddles, comms, the main AR2412 stage box, the AHM-64 processor, and the power amplifiers for the foldback and front fill systems, as well as the wireless mic packs and all the required accessories for outfitting them to the singers.

The deck sound (A2) position entailed prepping all the packs and mic elements each day for all the singers, as well as managing batteries and comms. Since most of the production’s singers were not familiar with being miked, Hannah would work closely with them each day to ensure that they were fitted comfortably, addressing any issues they had and also ensuring consistent placement so as to maintain the sound quality of the mix.

Although she’s a skilled audio professional, this was her first time working in this capacity and I’ve invited her to share some of her thoughts and observations on this work:

“Having never worked on any theatre productions like this before, the premise of properly placing mics on these opera singers who most of whom had never dealt with mics before was daunting,” she says. “Prior to the opera, I spent time talking with some experienced friends, researching, and debating over best techniques. The night before we loaded in the show, I practiced miking up Michael a few times in his dining room. I spent a lot of time leading up to the show learning about how this is done in other productions, looking up pictures and watching videos.

“Once we actually got to the venue and the singers came over to my position to be miked, I discussed initial placements with Michael and fumbled through the first few people. As the week went by I felt myself settle into the job. I got better at placing the wig clips in the part of each singer’s hair so it was concealed better.

“Comparing my work from the first rehearsal against that of the final show, the difference in actual placement of the elements themselves (and how the placement lasted through the performance) as well as the way I was able to conceal the wire in each singer’s hair was a vast improvement.

“When a mic inevitably broke during the show, I was able to switch it out with ease,” she concludes. “It was in that moment I realized that I had really improved and gained this new skill. I had a blast working on this production, and I’m appreciative of the experience and knowledge I’ve gained as a result.

We were also happy to have a production sound intern working with us on this show – Shannon Scally, who is studying theater at SUNY Fredonia college. She was very enthusiastic about learning as much as she could, and I enjoyed having her participating with us. I walked her through my design process for the sound system and showed her how my console file was laid out.

During the show run, Shannon would start the day assisting Hannah with mic prep in the deck sound tent, and once the show began, she would sit with me at the console, assisting with the mix, being my “eyes and ears” to communicate with stage management and other departments, and learned to mix one of the arias from the show.

I always appreciate having someone to learn/intern/shadow me while I’m working – it’s a great opportunity to pass along some knowledge, share my approaches, and foster passion for live event production – all things that I was lucky enough to have great mentors for, and things that I feel strongly about “paying forward” as I advance in my own professional journey.