.

Signal path refers to the path that sound makes while being processed.

Recording signal paths include:

Sound Source > Capturing Device > Wire From Capturing Device To Console Channel Input > Channel Volume, EQ, Etc. > Channel Output To Recorder Track

Mixing signal paths include:

Recorder Track To Console Channel Input > Channel Processing, Volume, Pan, Etc. > Channel Output To Stereo Bus > Main Stereo Output Master Fader > Final Mix

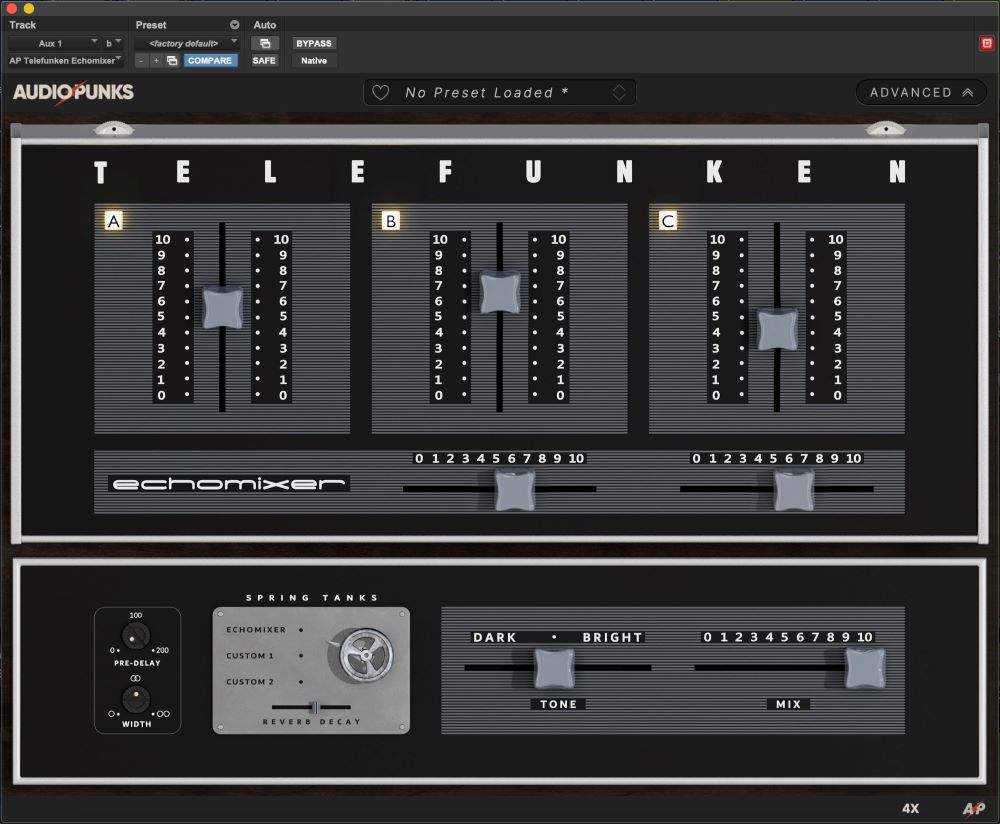

In addition, mixing signal paths include:

Channel Output To Audio Bus Through Aux Sends > Aux Channel With The Send Feeding Into It > Processing > Aux Channel Output To Stereo Bus, Etc.

Gain (volume) refers to the way that the volume of a sound will increase and decrease as it goes through the different stages of a recording or mixing path.

Gain structure refers to the input and output levels of each stage of the path. While it’s possible to set gain/volume knobs to anything and at the very last knob turn things down if necessary, you’ll most likely have inefficient gain structure that can cause extra noise to be added in one stage, and even overloading in another.

Unity gain means that a path or even stage of the path has the same volume going out as it did coming in. Although setting a knob or fader at zero will usually provide unity gain, once you start to process a sound you end up changing the volume within that particular stage of the path. You’ll then most likely have to adjust a different stage of the path to compensate.

Many do not understand gain structure and end up overloading early stages, turning the sound down later and not knowing why their meter level is “in the green” but the sound is distorted.

Changing gain means decreasing it (which can be done passively but is usually done using electronics) or increasing it (using electronics to amplify it). Every process a sound goes through will change the tone of the sound, even if the process is a little bit of gain change.

Imagine pouring water from glass to glass in a long row of different sized glasses, and you only have the first glass of pure water and a hose with dirty water. As you pour water from the first glass into the second and from the second into the third (and so on), some of the glasses will change the overall amount of water that is being transferred.

One glass may be wider so the water poured in from a narrower glass would not be enough to fill it, and then hose water would be needed to top it off. This would be the same as turning up a fader or knob on a channel to make a quiet sound louder. The amount of what you’re working with has increased to a desirable amount, but the purity of what you’re working with has been diluted by the dirty water or sound changes of the audio components.

Another glass may be filled with rocks and so the water it cannot hold spills out, reducing the amount of water you have. This is the same as using a fader or knob to make a loud sound quieter. Note that the purity of what you have is not changed. There are audio components that reduce sound (using passive resistors) without changing the sound, unlike active amplifiers that increase sound and noise.

Thus the volume will change throughout the chain, and so will the purity at different stages. Of course you want your first glass (the first volume control the sound source hits) to be as full as possible so you have a better chance or retaining sound purity through to the end of the chain.

However, be careful. All stages have maximum allowable volumes at their input (and within their processing) that will result in distortion that will be passed down the chain. Imagine overloading your second glass, which adds red dye to the water. No volume changes down the chain will ever get rid of the red dye.

Big processing (even volume) means big changes in sound. With a good gain structure, there’s usually not much need to add volume in the chain, helping to keep sound as “pure” as possible. And it’s important to start with a good-sounding first stage, which is where most of the volume increasing should be done.

Finally, always look out for distortion at every stage of the audio chain. You’re better off dealing with the extra noise on a quiet clean sound than the distortion on a good volume sound.