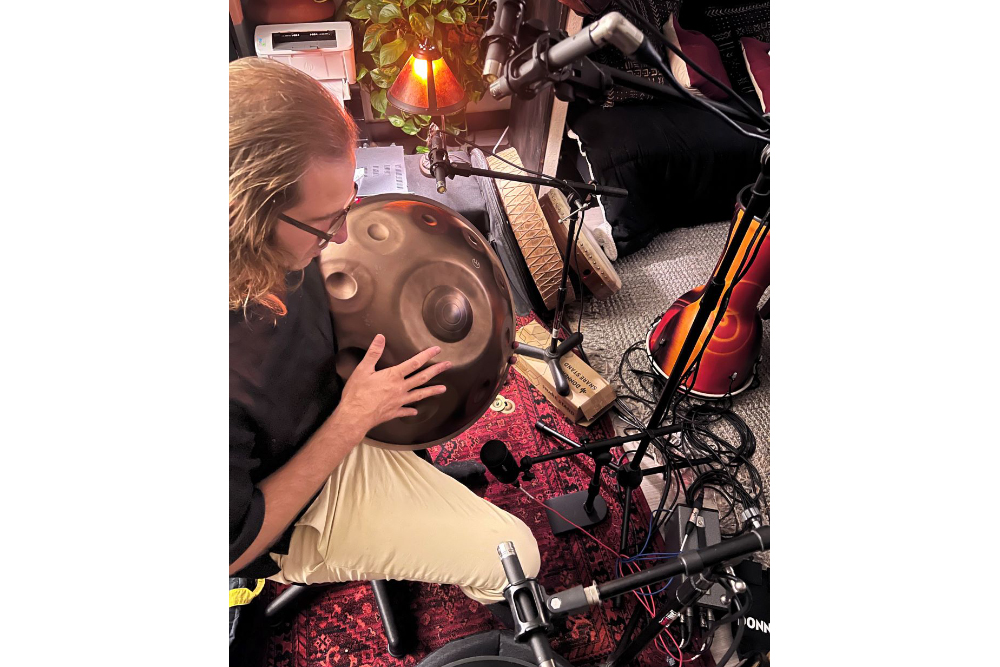

Sometimes when recording, microphone placement can seem either too difficult or way too easy. As with most things in life, it’s really somewhere in the middle, but sometimes it’s not very easy to get there.

Here’s an excerpt from the newly released Recording Engineer’s Handbook Third Edition that shows five simple miking techniques that will help you get a bigger and more accurate sound.

Before you start swapping gear, know that the three most important factors in getting the sound you want are mic position, mic position and mic position.

Get the instrument to make the sound you want to record first, then use the cover-your-ears technique to find the sweet spot, position the mic, then listen. Remember that if you can’t hear it, you can’t record it.

Don’t be afraid to repeat as much as necessary, or to experiment if you’re not getting the results you want.

That said, the following are some general issues and techniques to consider before placing a mic:

1. One of the reasons for close-miking is to avoid leakage into other mics, which means that the engineer can have more flexibility later in balancing the ensemble in the mix. That said, give the mic as much distance from the source as possible in order to let the sound develop, and be captured, naturally.

2. Mics can’t effectively be placed by sight until you have experience with the player, the room you’re recording in, the mics you’re using, and the signal path. If at least one of these elements is unknown, at least some experimentation is in order until the best placement is found. It’s okay to start from a place that you know has worked in the past, but be prepared to experiment with the placement a bit since each instrument and situation is different.

3. If the reflections of the room are important to the final sound, start with any mics that are used to pick up the room first, then add the mics that act as support to the room mics.

4. From 200 Hz to 600 Hz is where the proximity effect often shows up and is one reason why many engineers continually cut EQ in this range. If many directional microphones are being used in a close fashion, they will all be subject to proximity effect. and you should expect a buildup of this frequency range in the mix as a result.

5. One way to capture a larger than life sound is by recording a sound that is softer than the recording will most likely be played back. For electric guitars for instance, sometimes a small 5-watt amp into an 8-inch speaker can sound larger than a cranked full Marshall stack.

Bobby Owsinski is an author, producer, music industry veteran and technical consultant who has written numerous books covering all aspects of audio recording. For more information be sure to check out his website and blogs. Get the Recording Engineer’s Handbook Third Edition here.