Befriend your local steel warehouse owner, bring two associates, and prepare to listen. Most steel sheets come in 3-foot wide sheets; this is close enough to 1 meter for our purposes.

The length, however, is usually 8 feet, and cutting charges to make it 6 feet might be added to the price of the steel. Some places also have minimum orders, so try to buy your plate and frame materials from the same source to save added expense.

If the owner of the shop will allow (and it’s worth a healthy tip to have him help you out), have your two friends hold the sheet of steel horizontally as tight and still as possible, such that it doesn’t “thunder.” Tap it in the center with a key and listen for a “sizzle” and long decay in the high frequency, as opposed to a “clangy” sound. The delicacy and length of the high-frequency decay are what you are really after, since the bottom and mids can be dealt with more successfully by tensioning.

Try several pieces of different types until you find what you want. Be selective and take as much time as possible, because this is the heart of your system and you must be happy with it.

Including the cutting, the steel sheet should run between $50 and $100, depending on the type you choose. Reinforcing the corners by spot welding a triangular piece of steel on each one is the recommended procedure. For corner-cutting by the cost conscious, however, it’s not totally necessary, since this can run an additional $25 to $50.

However, it really should be done if at all possible, because the plate will be put under heavy tension, and holes will be drilled in those corners later in the plate-preparation procedure. The holes should be drilled after the frame is completed, so a more “custom” fit may be made.

The Frame

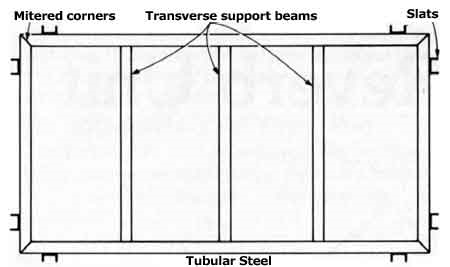

The frame is simply 1 to 1–1/2 inch tubular steel, either round or rectangular-shaped, and welded together at the (preferably mitered) corners. Simple angle iron can be used, if absolutely necessary.

The frame should be reinforced by three transverse beams (Figure 1). Near both sides of each of the four corners (eight all together), weld flat pieces or slats of steel, which may be channeled for extra strength.

Note that Joe and I enhanced the design by adding 2 extra tensioning slats in the center of the long dimension of the frame, to assist in the tuning of the plate.

The slats should extend 1-1/2 to 2 inches beyond the frame, and be about 1 to 2 inches from the corners. Holes will also be drilled in the center of each of the slats.

To determine the exact placement of the holes in the slats and in the plate, as well as the exact measurement of the length of the tubular steel for the frame, you must make sure the plate and the frame line up together.

Make the inside measurement of the frame 1 to 1-1/2 inches larger than the dimensions of the plate. Then lay the plate on top of the frame.

On the plate, mark the eight spots where the holes will be drilled. Then mark the frame where the eight slats will be welded. Next, mark the slats where the holes will be drilled. When all the holes are drilled and the slats welded in place, paint the frame to stop rust and corrosion.

The next step is to suspend the plate in the frame. EMT used spring clips that held the plate in place and were also used to determine tensioning. These are weak, and often snap.

One of the improvements made by most plate manufacturers was to use stronger, heavier clips or hooks. Ecoplate used clips similar to those that secure fiber straps used on packages.

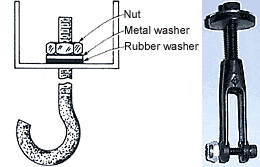

We will use simple, tempered, hardened-steel hooks, threaded on their shafts. (Joe and I now utilize fiberglass clevis yokes with machine shop quality allen bolts to better control the tensioning and Plate/Frame isolation.)

If the hook is plastic-coated, and hard-rubber and metal washers are used, the plate and the frame can be totally isolated as far as direct metal-to-metal contact goes. To suspend the plate, you will probably need help getting the hooks through the holes in the plate.

Slip the shaft of each hook through the holes in the slat; thread the washers and a nut of the correct size on the hook shafts, and hand-tighten all nuts (Figure 2). The plate can now be suspended from the frame.

Now comes the subjective and fun part of the project-mounting the driver and pickups, and tuning the plate.

The Driver

EMT, Ecoplate, and Lawson all used similar drivers. A bullet-shaped metal moving-coil “slug” is screwed into the plate. Two wires carrying the signal go to the coil and it is suspended in a large, heavy, circular magnet (Figure 3).

It’s important to be sure the moving coil assembly does not rub or touch against the sides of the magnet. The coil and magnet are aligned using a plastic alignment disk. The procedure is delicate, and transporting the unit sometimes misaligns the driver/magnet assembly.

Stocktronics and Audi-ence both used a wire rod attached to the plate on one end, and to the voice coil of a speaker on the other. It can be moved with no realignment, since there is plenty of “play” in the movement of the rod, and this is restricted to within limits by a rubber guide.

The system we use is similar to both, but unique unto itself. It is also one of the main reasons that this plate can be built so reasonably. This design uses a specially designed driver-similar to what used to be offered as a “coneless speaker” several years ago.

Whatever the driver is attached to becomes the “sounding board” and vibrates enough to reproduce sound. Therefore, if screwed into a door, that door would become a “speaker.”

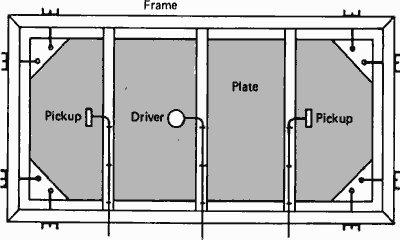

The specially designed driver (Figure 4) is an improved version of the coneless speaker. To install the driver, simply drill a small hole, the size for the screw on the driver, in the center of the plate 2-1/2 inches off to one side of the center of the beam of the frame.

Screw the driver in the side of the plate, with the frame reinforcements toward you, about half way until tight. Attach a speaker cable to the two terminals on the driver. Be neat and run the cable down the reinforcement with “ty-raps” or tape.

Now the fun begins. Move the plate into your studio. Make sure it is standing upright. Connect the other end of the speaker cable attached to the driver to the output of your cue (headphone), or dedicated tube, class A, MOSFET, etc., amplifier.

Put on a tape with a steady snare-drum track or a constant vocal track. Send only the selected track to your cue and, voila, the signal will be heard on the plate. Assuming it’s the snare track, what you should hear is a thunderous snare sound similar to “Bridge Over Troubled Water” or “The Boxer” by Simon and Garfunkel (although I think they used an elevator shaft for their reverb chamber).

But, anyway, congratulations! You have a working plate reverb!

Now comes another fun part — using your opinions, taste, and ego to get it to sound just the way you want. This will require your choice of pickups as well as tuning and equalization.

Pickups

All the commercial units use piezoelectric pickups or accelerometers. These are basically contact mic/pickups and are available from several manufacturers.

As a matter of fact, you probably already own one, or at least know someone who does. Examples of available units are those from Barcus-Berry, Fishman, and Frap. Some pickups need no preamp and can be plugged into the echo return(s) on your board.

You can also return the output of the pickups through two mic inputs on your mixer, using a tube, discrete class A, transformer or transformerless (differential), FET, IC DI. These are some of the variables that you must work out depending on the console you own, and the pickups you use. Try as many pickups as you can borrow until you find one that you like and that easily interfaces with your mixer.

For a mono reverb, place the pickup near one of the side frame reinforcements. Experiment by moving the pickup up around, and down, on both sides of the reinforcement, until you find the spot you like.

Then secure the pickup by epoxy, wax, putty, or whatever the pickup manufacturer recommends. Run the pickup wire down the reinforcement, again using “ty–raps” or tape. For a stereo unit, do the same thing on the other side (Figure 5).

Tuning The Plate

With the pickups in place, the plate itself now comes into focus for tuning. In theory, think of the plate as similar to a drum head. Also, correct tuning means all the lugs are equally tensioned.

So, start by holding the hooks suspending the plate in the frame with a pair of “vice grips” or similar pliers, and tighten the nut on that hook with a ratchet wrench. Do this evenly around all eight hooks.

How do you know when the plate is tuned? Good question. You don’t, really, because every manufacturer used their own method for tuning.

EMT shipped units pre-tuned except for four nuts, which were supposed to be tightened by exactly 1/4 turn when installed. Most independent EMT servicepeople will tell you to tighten each one until a spring suspension clip breaks, and then replace it and tighten until 1/8 of a turn before it breaks again!

Lawson and Audi-ence shipped their units pre-tuned, no adjustment necessary. Ecoplate supplied a spring gauge and specified pushing the gauge against the plate at all eight plate tensioning points, until there was approximately 150 pounds of pressure at each point.

As a total contrast, Stocktronics used no tuning at all, claiming the steel was pre-stretched/tuned during manufacturing. In fact, their plate was simply suspended by six springs in a very light aluminum frame.

Which method is correct? Any/all/none, depending on your point of view. One thing is certain, though. If you like the way it sounds, it’s right. So I suggest tuning by ear.

Remember, the tighter the plate, the tighter the bottom. It is usually better to over-tension than under-tension. Also, listen for “flutters” or “beats” (like two slightly out-of-tune guitar strings) on the decay of the reverb, and even-out the tension until they disappear. EMT warned about the “oil can effect,” a very metallic sound that is heard on an obviously out-of-tune plate.

What I suggest is to find an existing plate you like in a studio near where you live. Rent an hour of time, and bring along a tape of various tracks-snare alone, drum kit, congas, tambourine, voices, piano, and run it through the plate.