It’s inconceivable nowadays that a band would perform a live show without stage monitors, but in the early days of rock ‘n’ roll, that’s exactly what used to happen. In the early 1960s, sound systems were very basic and used primarily to amplify the vocals, and monitors had not yet been invented.

Musicians had to rely on their instrument amplifiers to hear themselves and singers were at the mercy of whatever they could hear from the sides of the PA and room reflections – which was, of course, subject to acoustic delay, making it a herculean task for the singer to stay in time with the band. Needless to say, it made performing a pretty miserable experience, so much so that it was a large part of the Beatles’ decision to quit touring in 1966 – PAs were insufficient for the audience to hear them, and they couldn’t hear themselves.

Numerous live sound engineers were trying to find a solution to the problem, and several came up with the idea of stage fills around the same time. Far from the independently mixed stage fills we see today, however, these were simply a pair of loudspeakers at the sides of the stage driven by the house mix, as early mixing consoles weren’t equipped with auxiliary sends.

One of the first recognized times that “foldback” – literally a mix “folded back” to the stage from FOH – was deployed came in 1961 for a performance by Judy Garland at the San Francisco Civic Auditorium, courtesy of McCune Audio. The Beatles got to hear a little of themselves in 1965 when Duke Mewborn of Baker Audio used left and right arrays of Altec-Lansing loudspeakers for both the PA and stage fills at a stadium in Atlanta.

The Who engineer Bob Pridden estimates it was back in 1969 that he and the band first began experimenting with stage sound. “We just started thinking, ‘How can we hear ourselves?’” he says. “And then I got an amp with a volume control and turned two speakers with the full mix inwards across the stage, like two side fills. Then I just took it down a bit so it didn’t feed back, and that really was the beginning of monitors.”

The “father of festival sound,” Bill Hanley (who pioneered sound systems at the original Woodstock in 1969 as the the iconic Newport Folk and Jazz Festival) is widely credited with the concept of a loudspeaker on the floor angled up at the performer with directional microphones to allow louder volumes with less feedback, an idea born when he was working with Neil Young and Buffalo Springfield in 1969.

Hanley is famously credited with playing a key role in coming up with the design for wedge floor monitors. How did those first wedges come into existence? “Oh crikey, I don’t know how we came up with them!” he laughs. “They were really antique at the time though. They looked like rabbit hutches and that’s what I used to call them. They were just these boxes on the stage with wire grilles. The first wedges we had were made by a company called TASCO. The horn was in another box you clipped on the top but they were always falling off and what have you.

“Then, of course, they got more and more developed and we started using a company in America called Showco. They were the first really great monitors. We bought some from them and used them all around the world. They were absolutely great – huge wedges – but the sound was superb! I think we had about eight of them and then, from there, we went to using Clair Brothers and their wedges.”

Wedges On The Rise

As PA systems increased in size, and multichannel mixing consoles meant that there was more than just a vocal going into the PA, the increased sound levels out front meant that monitors became even more of a necessity for performers. Wedge-shaped loudspeakers such as those developed by Showco and Clair started appearing on stages, and once musicians heard of them, they all wanted a piece of the action.

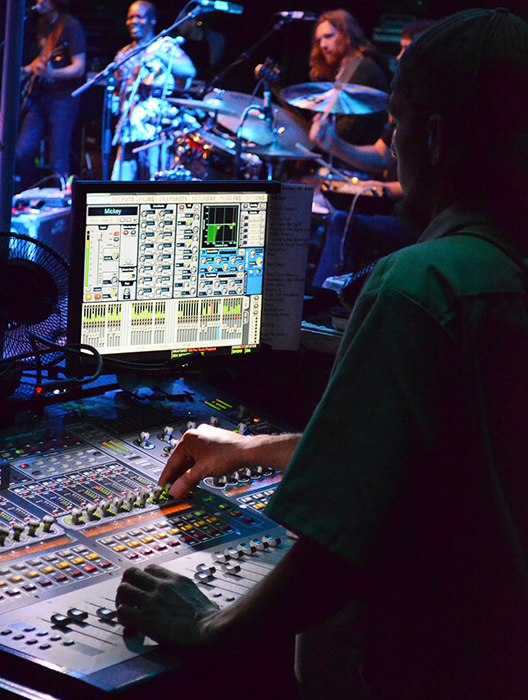

The need for a separate monitor engineer who could solely take care of the band soon became apparent, and in the 1970s Bob Cavin, chief engineer at McCune, designed the first monitor mixer designed expressly for stage monitoring. It’s interesting to note that such additions were not always welcomed by front of house engineers. Pink Floyd engineer Mick Kluczynski observed that wedge monitors spread “like a virus” and he quickly found himself battling a secondary sound system, struggling for control of the main mix. (FOH versus monitors was underway!)

As house systems continued to grow ever larger and more sophisticated, and with increased sound pressure levels, the sheer volume of stage and PA sound meant that performers were once again struggling to hear themselves accurately, alongside a new problem which had presented itself: that of gig-related hearing damage. What could be done?