A couple of years ago, I was busy grading a batch of reports from my second-year acoustics students where they were tasked with redesigning a run-down music venue in terms of internal acoustics and noise pollution. In addition, they had to specify a suitable sound system for the space. There was a common approach used for the subwoofer system design in many of the reports; one which, if implemented, would be counterproductive to what the students were trying to achieve.

Many students came up with the idea that to save space, they’d place the subwoofers underneath the stage. To ensure musicians on stage have a reasonable working environment, they specified that the subs should have a cardioid polar response (something which features in a number of current units on the market).

At first glance, this seems logical. There’s a big problem, however…

Interactions & Other Factors

When a cardioid sub is placed underneath a stage, it will lose the majority of its directivity, more or less becoming an omnidirectional source. This is due to the interaction between the source’s output and reflections from the stage (which will wreak havoc on the intended interaction between the front- and rear-moving sound waves).

In addition, a stage could resonate due to the close proximity of the subwoofers, causing further issues (in my experience, temporary staging is very good at resonating around 120 to 160 Hz, likely a higher harmonic of the driving fundamental frequency originating from the subs).

Interestingly, the students’ approach to cardioid sub placement demonstrates the same misunderstanding I often encounter when talking to practitioners. It’s blindly (or deafly?) assumed that cardioid subs will retain their polar response no matter what.

Thinking back to when I started working with Gand Concert Sound (Elk Grove Village, IL), I remember a couple of product design engineers from NEXO visiting us. During our conversations they very clearly explained that the company’s CD18 subs need roughly 6 feet of open air around them to maintain their intended polar response. There were many sketches on the back of napkins passed around and it made perfect sense. I suspect this lesson hasn’t quite reached everyone in the industry.

A few years later, I was spending my non-summertime working towards a PhD at the University of Essex (UK) under the supervision of Professor Malcolm Hawksford. Since the research was focused on the analysis, modeling and optimization of low-frequency sound reproduction and reinforcement, I was able to investigate a number of questions that had come up while working with Gand – namely that of cardioid subs under stages.

Using my electroacoustic modeling software (now called LowFAT), I simulated a number of sub and stage configurations. The results were clear: directionality is destroyed when a cardioid sub is placed underneath a stage. Moving a sub even one meter in front of a stage results in the expected cardioid response. This being a minor point in a paper I was working on, I left it at that.

Measuring It

A number of years later, now having moved to the University of Derby (UK), out of interest I had one of my final year undergraduate students, Joe Paul, focus his dissertation research on practical experiments to better illustrate this issue. We started by measuring a cardioid in a large room (roughly 30 x 30 feet). Don’t judge – it’s located in the midlands in England where we usually only get a couple weeks of good weather and that’s in the summer when most of us are away from the university.

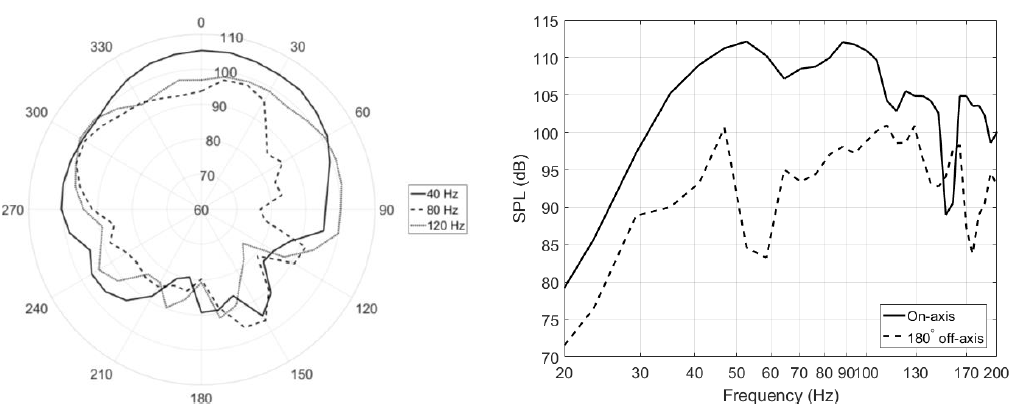

In our test space, the measured front-to-back rejection of the cardioid sub at 40 Hz, 80 Hz and 120 Hz was 16 dB, 14 dB and 16 dB, respectively (Figure 1). From documentation provided by the company, the predicted front-to-back rejection is 17 dB. So far, so good.

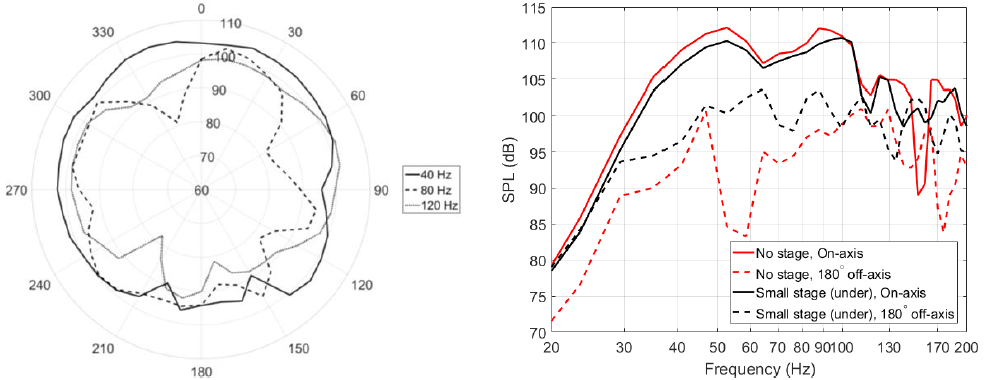

Next, we placed a single piece of stage deck (8 x 4 feet) over the sub and repeated the measurements (Figure 2). We can see that the front-to-back rejection of the sub has significantly reduced. The most significant issue is seen at 55 Hz, where rejection is approximately 15 dB worse than before the deck was put in place.

As a side note, the on-axis (in front of the stage) response is roughly the same as without the stage, so the audience experience isn’t changed by stage effects, it’s just the stage personnel that suffer.

Following the manufacturer recommendations, we then moved the stage so that the subwoofer was slightly in front of the stage (no part of it was underneath) and repeated the measurements (Figure 3). Now we found ourselves back to where we started. The sub behaved as expected. And there was much rejoicing.

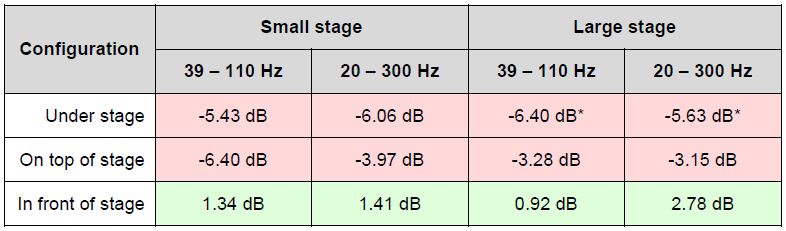

We carried on with the experiments to include a larger stage (a 3 x 3 grid of 8- x 4-foot pieces of deck) as well as testing for sub placement on the front edge of the stage. To summarize our findings, Table 1 indicates front-to-back rejection for each test configuration with reference to the rejection achieved with no stage present. A value of 0 dB indicates that the rejection perfectly matches that without a stage present. Negative values indicate a reduction in rejection. (Note that * indicates simulated results using LowFAT, which was required due to experimental limitations.)

The reason behind testing two frequency bands was to inspect the sub range exclusively (39 – 110 Hz for this unit) and then to look at a bigger picture (20 – 300 Hz), which picks up stage resonances and other negative effects.

More Going On

For a little while, this seemed to be the only focused experiments published in this area. Luckily, my colleague, Simon Lewis, discovered work by an Italian firm which replicated our experiments in late 2017. (That report can be found at illatooscurodellafase.wordpress.com.) In this case, the tests were conducted outdoors with a simplified stage (plywood was used). Results seem to indicate that the degradation of the cardioid response is even more pronounced than our experiments had shown!

Recent experiments by Kees Neervoort from Event Acoustics (Netherlands) once again replicated my original results and expanded the scope of the problem finding that stage “catwalks” further degrade sub directionality.

This isn’t quite the end of the story, though. There’s something else to keep in mind. Most festival stages have stage skirts to improve the “look” of the event. It’s important to check whether these are acoustically transparent or not. If they aren’t, you’ll find that sub output will decrease drastically.

This is due to the reflection coming off the stage skirt. The reflection, when it reaches the front of the subs, will be significantly out of phase from the direct sound (the precise relationship is strongly frequency dependent). This will cause partial cancellation of the forward-moving wave, thus reducing efficiency. This effect was recently confirmed experimentally at a mock live event as part of the above-mentioned research conducted at Event Acoustics.

The same goes if you’re indoors and place a cardioid subwoofer against a wall. I ran into this situation when on a gig with Adam Rosenthal a number of years ago at Chicago’s Auditorium Theater. The only place we could put the NEXO CD18 subs was on the offstage wings in front of the proscenium.

When we fired up the system, the low frequencies seemed to be extremely low level even though we were driving the system fairly hard. After thinking about it for a few minutes, we realized that the reflection off the proscenium was cancelling out our direct sound.

The solution? Turn off the rear drive unit, making the CD18s omnidirectional. After that, the low-frequency content came back to the expected levels and we had a good show. So, what are the takeaway messages here?

— Don’t place directional subs underneath a stage.

— Don’t place directional subs in front of a wall.

— Beware of non-acoustically transparent stage skirts.

— Do place directional subs slightly in front of a stage (about 3 feet of clearance is recommended).

As a final note, in case you think all of this stuff is new and I’m brilliant for highlighting these issues, I should note that Harry Olson and Richard Waterhouse figured out just about all of this before most of us (and even some of our parents and grandparents) were born. Read their papers and books! There’s nothing new here…

Academic papers this article is based on:

Hill, A.J.; J. Paul. The effect of performance stages on subwoofer polar and frequency responses. Proc. Institute of Acoustics – Conference on Reproduced Sound, Southampton, UK. November, 2016.

Hill, A.J.; M.O.J. Hawksford, A.P. Rosenthal; G. Gand. Subwoofer positioning, orientation and calibration for large-scale sound reinforcement. 128th AES Convention, London, UK. May, 2010.

And, selected “historical” reading:

Olson, H.F. Elements of Acoustical Engineering, 2nd Edition. D. Van Nostrand Company, New York. 1957.

Waterhouse, R.V. Output of a sound source in a reverberation chamber and other reflecting environments. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, vol. 30, no. 1, pp. 4-13. January, 1958.