Electronic keyboards, the start of it all. Right from the beginning of modern concert sound, DI boxes have played an essential role in getting the sound from the stage to the PA system.

Probably the most iconic “direct” instrument of all was the Fender Rhodes. Harold Rhodes started developing the idea as far back as the 1950s, but it was in 1970 that the Rhodes Stage piano took the concert stage bringing the first “portable” keyboard to market.

The original Rhodes piano tone was created by a piano-like hammer striking a “tine” that would vibrate up and down in front of a magnet to create the tone—very much the same way an electric guitar string vibrates atop a magnetic pickup. One would adjust the tone by changing the “tine-to-magnet” relationship.

And like an electric guitar, the output from the suitcase was not amplified (or buffered) in any way. So the output from the piano was generally sent to a guitar amp where it was mic’d.

Some years later, the first active DI boxes came round. They didn’t load the Rhodes pickups, which made it practical to send the “direct” sound to the PA system and monitors.

But something happened. That something was Keith Emerson and Rick Wakeman, and the Moog synthesizer, which found its way out of the electronic music department to the stage. These guys no longer had one or two keyboards—they had racks of them!

The Arp 2600 and String Ensemble, Oberheim, Korg, the venerable Sequential Circuits Prophet 5 – it was an analog explosion. Everyone had a Rhodes (or Wurlitzer) and a bunch of synths.

Fast forward to 1981, and Yamaha introduced the DX7, which would go on to become one of the most successful keyboards ever. It brought along something totally new: frequency modulated digital technology. Now you could get a bell-like Rhodes sound without the weight.

The world then changed again with the E-MU and the Akai S900 digital sampler. All of a sudden, we had complete orchestration, real sounding piano samples, and digitally sampled drum tracks were everywhere. There was no going back.

Relatively Powerful

Today, pretty much all keyboards and drum machines are digital, and can basically be thought of as keyboard controlled CD players. And like a CD player, the output from a digital synthesizer is relatively powerful when compared to an electric guitar or an old Rhodes piano.

Because they’re so “loud,” they needed headroom to operate, meaning that the old active DI box that may have been a boon to the low-output Rhodes piano can no longer keep up.

The headroom is limited by the internal battery or limited by the low current afforded by phantom power. To make matters worse, unlike a CD that is processed and compressed before it is mass produced, digital samplers are raw. They can generate huge transients that will overload most active DI boxes, and end up distorting horribly.

The problem is further exacerbated with digital pianos. These full-range devices are not only very dynamic, they have a frequency range that starts way down low and goes up forever.

To handle modern keyboards, there are two choices:

1) Send the keyboards into a mixing console where the internal rail voltage is sufficiently ample that it is able to handle the range.

2) Send the signal to a passive direct box where the headroom is not limited by the current afforded to them. Passive DI boxes are different- they use transformers.

Phantom Of The Power

Replace the diesel engine inside a dump truck with a 4-cylinder car engine and fill the truck with gravel. What will happen? Nothing. The engine will be unable to handle the load.

The same applies to phantom power. Folks tend to “believe” that if it’s active, it must be good. But the truth is, phantom power was never designed to power direct boxes.

Phantom was invented by Mr. Neumann as a means to charge the capsules on his microphones. He needed a lot of voltage (48 volts) and very little current (5 milliamps).

A quality preamp requires +/- 16 volts (32-volt swing) and about 50 milliamps of current. With 1/10th the current, it’s like trying to run a dump truck with a motorcycle engine.

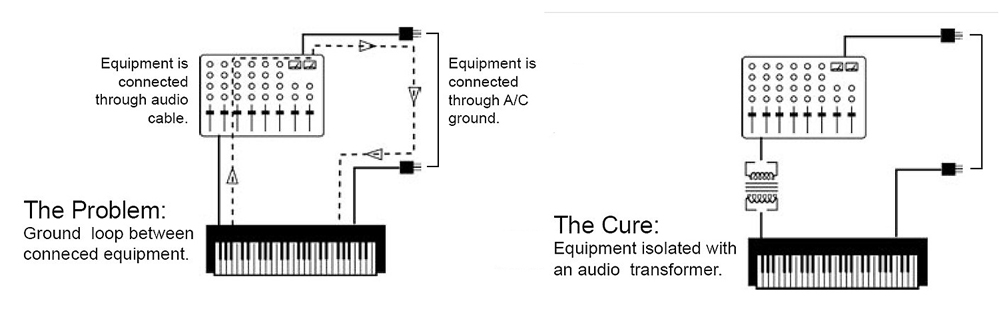

Passive direct boxes are not power limited. They’re old-fashioned devices that basically combine a couple rolls of wire (coils) with a chunk of metal (the core).

A DI has the task of converting a high-impedance signal to a low-impedance balanced signal where it can be managed by the mic splitter and mixing console’s preamp.

With keyboards, current enters the transformer where the conversion occurs. But instead of overloading. like an active circuit, transformers distort gradually. More precisely, they don’t so much distort as saturate.

We often say that transformers sound “vintage” or have a limiting quality about them. This is because good quality transformers generate warm sounding even order harmonics, or what is commonly known as a warm Bessel Curve.

Thus the reason highly dynamic buffered signals like digital keyboards sound great when they are used with a passive direct box.

Multiple Choices

Mono, stereo or multichannel – which DI is best? It depends upon your point of view.

If audience members are sitting right in front of the left PA loudspeaker, they will be unable to hear what is coming out of the right PA loudspeaker. Will they benefit from stereo? Probably not.

Stereo may sound great in the practice room or be invigorating on stage, but in most live venues, it is rarely enjoyed by all. The advantage that a stereo DI brings is capturing the stereo sample without having to reprogram the synth.

And if you do decide to have a stereo rig on stage, a stereo DI allows the house engineer to mix both channels and pan them stereo (if beneficial).

A stereo DI is often used at the output of a keyboard mixer. Here’s why: on a stage, all of the microphones go to a mic splitter before the signal is sent to the house mix position. Mic splitters are designed to handle mic levels, typically around -50 dB. A keyboard produces a -10 dB signal while a mixer can produce +4 dB or more.

This excessive level will cause the mic splitter to overload. The pad on a direct box lowers the output so that it matches that of a microphone and protects the mic splitter from being overloaded by the mixer. Multichannel direct boxes bring forth the added advantage of independent control over each instrument.

Here’s the deal: when you mix the sound so that it is comfortable on stage, it may in fact not be ideal for front of house. In other words, you may find that you need extra jam to hear your piano on stage, and have the string synth pushed back in the mix.

But in the arena, the piano-to-string volume ratio may not sit well with the rest of the band. What happens? The keyboard mix gets pushed back.

When you have the luxury of sending independent keyboard signals to front of house, the mix engineer is allowed to orchestrate. With more control, the engineer can decide how much piano fits and if the strings are too loud, can simply back them off.

Who would have ever thought that a DI would have so many twists and turns, especially after being around for more than 40 years!