You patch in a piece of audio equipment, and there it is: HUM! This annoying sound is a common occurrence in sound systems.

Hum is an unwanted 60 Hz tone—50 Hz in Europe—maybe with harmonics. If the harmonics are especially strong, the hum becomes an edgy buzz.

A sound system also might be plagued by RFI (Radio Frequency Interference). It’s heard as buzzing, clicks, radio programs, or “hash” in the audio signal. RFI is caused by CB transmitters, computers, lightning, radar, radio and TV transmitters, industrial machines, cell phones, auto ignitions, stage lighting, and other sources.

This article looks at some causes and cures of hum and RFI. By following these suggestions, you can keep your audio clean.

HUM AND CABLES

One cause of hum is audio cables picking up magnetic and electrostatic hum fields radiated by power wiring in the walls of a room. Magnetic hum fields can couple by magnetic induction to audio cables, and electrostatic hum fields can couple capacitively to audio cables. Magnetic hum fields are directional and electrostatic hum fields are not.

Most audio cables are made of one or two insulated conductors (wires) surrounded by a fine-wire mesh shield that reduces electrostatically induced hum. The shield drains induced hum signals to ground when the cable is plugged in. Outside the shield is a plastic or rubber insulating jacket.

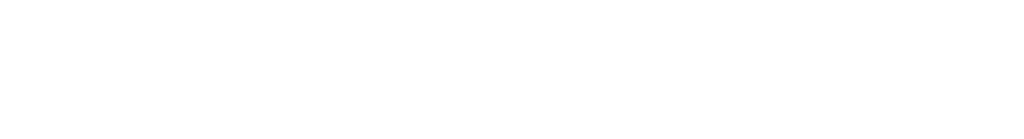

Cables are either balanced or unbalanced. A balanced line is a cable that uses two conductors to carry the signal, surrounded by a shield (Figure 1).

On each end of the cable is an XLR (3-pin pro audio) connector or TRS (tip-ring-sleeve) phone plug.

Each conductor has equal impedance to ground, and they are twisted together so they occupy about the same position in space on the average. Hum fields from power wiring radiate into each conductor equally, generating equal hum signals on the two conductors (more so if they are a twisted pair).

Those two hum signals cancel out at the input of your mixer, because it senses the difference in voltage between those two conductors—which is zero volts if the two hum signals are equal. That’s why balanced cables tend to pick up little or no hum.

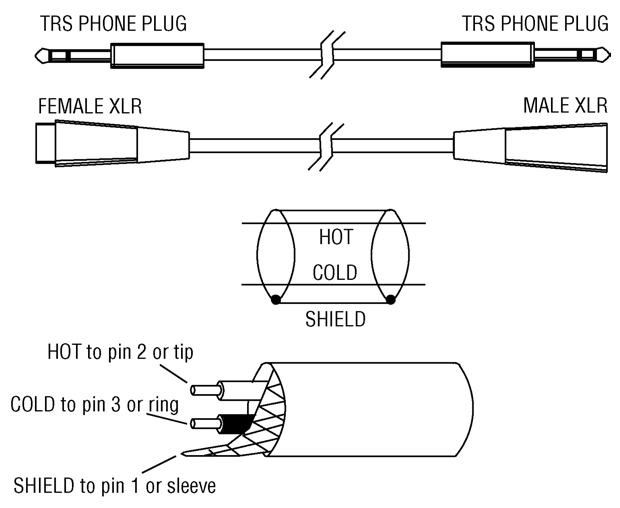

An unbalanced line has a single conductor surrounded by a shield (Figure 2).

At each end of the cable is a phone plug or RCA (phono) plug. The central conductor and the shield both carry the signal. They are at different impedances to ground, so they pick up different amounts of hum from nearby power wiring.

There’s a relatively big hum signal between hot and ground that results in more hum than you get with a balanced line of the same length.

Some hanging mics have long unbalanced cables, and some cables used between pieces of equipment are unbalanced. An unbalanced line less than 10 feet long usually does not pick up enough hum to be a problem.

Wherever you can, use balanced cables going into balanced equipment. Keep unbalanced cables as short as possible (but long enough so that you can service them). Check inside cable connectors to make sure that the shield and conductors are soldered to the connector terminals.

Route mic cables and patch cords away from power cords; separate them vertically where they cross. This prevents the power cords from inducing hum into the mic cables.

Also keep audio equipment and cables away from computer monitors, power amplifiers, lighting dimmers and power transformers. Keep mic cables and mic electronics well separated from lighting equipment in the grids.

Better yet, don’t use hanging mics. A few stage-floor mics and wireless mics will suffice.

GROUND LOOPS

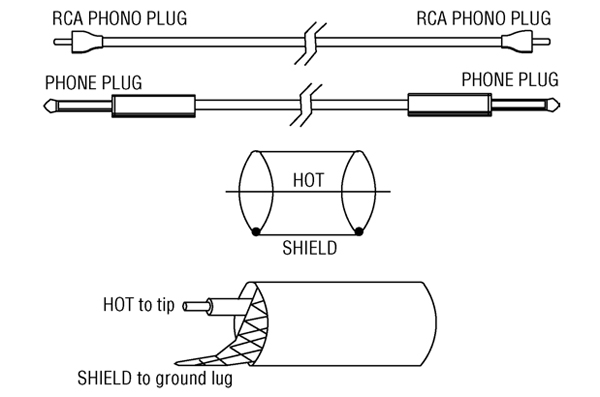

Another major cause of hum is a ground loop: a circuit made of ground wires. It can occur when two pieces of equipment are connected to the building’s safety ground through their power cords, and also are connected to each other through a cable shield (Figure 3).

The ground voltage may be slightly different at each piece of equipment, so a 50- or 60-Hz hum signal flows between the components along the cable shield. It becomes audible as hum. Also, the cable shield/safety ground loops acts like a big antenna, picking up radiated hum fields from power wiring.

For example, suppose your mixer’s power cord is plugged into a nearby AC outlet. The system power amplifiers are plugged into outlets on stage. So the mixer and amps are probably fed by two different circuit breakers at two different ground voltages. When you connect an audio cable between the mixer and power amps, you create a ground loop and hear hum.