This time out, we’re conquering a trio of common confusions about compression. Even the term can be troublesome. In the context of live sound, compression refers to a type of dynamics processing that acts to reduce the dynamic range of the signal; basically, reduce the difference between the loud parts and the soft parts.

However, in the recording and broadcast segments of the audio industry, there’s an additional type of compression: data rate compression, which deals with reducing the amount of bandwidth or space required to transmit or store a signal (like mp3, for instance). It’s important not to get the two confused, because they’re totally different concepts.

1. Compression makes things louder.

This one is closely related to another statement commonly made about compression: It brings up noise in a signal. In theory, this isn’t true, but in practice it usually is. Most compression used in live audio is downward-acting compression: When a signal’s level exceeds a threshold, the gain is temporarily reduced. When the signal’s level is below threshold, the signal is unaffected. So the compression process itself can only reduce gain, not increase it.

However, by reducing the peaks of a signal, the average level is also decreased, so it often sounds quieter. To address this, virtually all compressors include a Makeup Gain setting to restore the loss of level. The setting, being a simple gain stage, increases the signal level as a whole, so the entire signal level is brought up, including any noise that was already present.

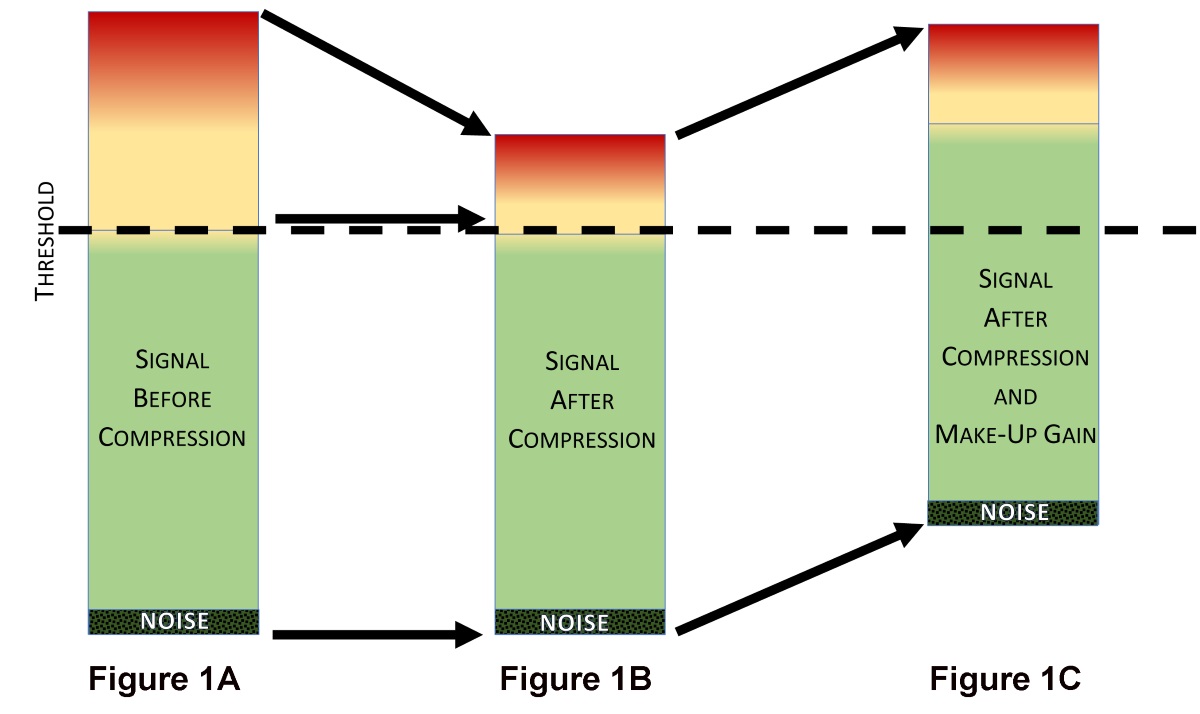

I’ve taken the liberty of employing my overwhelming competence with WordArt to create a visual aid. In Figure 1A, we start with an uncompressed signal. The dashed line represents the compressor’s threshold setting – the signal’s gain will be reduced when it exceeds this threshold. In Figure 1B, we see that compression has been applied only to the portion of the signal that exceeds the threshold. This example uses a 2:1 compression ratio.

Note that the below-threshold portion of the signal is unchanged, as is the noise floor at the bottom. In Figure 1C, makeup gain has been added, raising the entire signal by a set amount, noise and all. This is one reason why it’s not considered a great idea to add more makeup gain than necessary to compensate for the gain reduction.

2. Compression makes things sound punchier.

Unless we’re dealing with something exotic, compression works by reducing the level of the signal’s peaks. This can create a sensation of punchiness or richness when used modestly, but over-compression can really take the life out of a signal, as the excessive peak reduction can make it sound dull and lifeless. If a mix is lacking impact, or the drums don’t feel like they’re “hitting hard enough,” the solution is probably less compression, not more.

Skillfully applied compression can emphasize snare drum ghost notes and other “microdynamics” within the musical performance, but don’t overdo it. I’ve never heard a mix ruined by too little compression. Too much, on the other hand…

3. Mix bus compression can protect a sound system.

Not exactly. It’s a complicated topic, but basically the two causes of blown-up loudspeakers are over-excursion and heat.

Over-excursion is what happens with the loudspeaker diaphragm is forced too far forward or backward in its track. You know those loud “pop” and “bang” sounds that occur when someone stabs an open channel or punches on phantom power? Yeah, that’s the sound of the loudspeaker diaphragm being slammed around. This happens too quickly for a compressor to prevent, and it’s also a question of limiting the excursion and not letting the diaphragm travel any further, period. For this, a very fast-acting limiter is used. So the compressor’s out there.

Heat problems occur when the drivers are passing too much current over time, so an RMS limiter keeps tabs on that. Compressors reduce transients, which means the signal’s crest factor is reduced as well. This results in a more “dense” waveform that has a larger “area under the curve” and thus delivers more power to the loudspeaker’s voice coils.

The voice coils heat up and their resistance rises, passing less current from the amplifier. This causes a loss of perceived impact, which is added to the loss of perceived impact caused by reducing the transients in the signal. So the engineer cranks things up, and the spiral continues. It’s called power compression or thermal compression.

Short version? Mix bus compressors won’t protect your system, and they just might strain it a bit more.

Need an answer to a nagging bit of pro audio mythology? Send your questions to [email protected].