Choosing highlights from his time at the Grand Ole Opry is tough, says Bob Bussiere, the Opry’s in-house monitor engineer since 2016: “There’s so many. If I started rattling them off, I’d be doing an injustice to the ones I forgot to mention.”

Based in a purpose-built 4,000-seat theater southeast of downtown Nashville, the Opry has seen many historic moments in its 96-year history: it’s where Johnny Cash met June Carter, where Bill Monroe and his band invented bluegrass, where country greats such as Roy Acuff, Minnie Pearl, and Dolly Parton performed repeatedly… The weight of that history sometimes makes an artist’s first Opry performance nerve-wracking, but the Opry staff do everything they can to ensure every artist is as comfortable as possible.

There are times, Bussiere explains, when he avoids asking too many questions of artists: “Even, ‘Do your wedges sound good?’ Our shows are unique like no other. Pre-COVID, on Friday and Saturday night shows we’d sometimes see 16 different artists a night, with no soundchecks. There’s so much going on in their heads, so all I do is say ‘Welcome to our stage. If there’s anything we can do for you to have a better time let us know. Soak it in.’”

“It’s orchestrated chaos,” adds broadcast engineer King Williams. “It mostly looks like chaos, not orchestration, but it’s a system that’s been worked on for 96 years, a rubric all the artists who play here have to fit inside of. Sometimes that’s a shock to first timers, but when they see it work, they get it.”

That said, Bussiere notes, the sound team does sound checks when possible for artists making their debut. “To help out, even if it’s just them coming out alone, plugging in their guitar and singing, so when they play, they’re not totally freaked.”

Although that’s a relatively new thing, it’s in line with what the Opry describes as the secret to their old age and youthful spirit, namely, “Play it loose, make it fun, honor the music, and whatever happens onstage, roll with it.”

Moving Forward

The usual weekly schedule was derailed in 2020-2021 due to the pandemic, leading to the cancellation of both comparatively newer weekly and seasonal shows that included “The Friday Night Opry,” “The Tuesday Night Opry,” “Opry Country Classics,” and “The Wednesday Night Opry.”

But the flagship Saturday night show “The Grand Ole Opry” continued throughout and will celebrate its 5000th show on October 30, 2021. Through wars, the Great Depression, floods, and now a global pandemic – except for the week Martin Luther King was assassinated – the show’s run continuously since November 28, 1925, when WSM Radio introduced fiddle player Uncle Jimmy Thompson as the first performer on what was then called The WSM Barn Dance.

When the pandemic was declared, no one was certain what would happen, Bussiere says. “It was crazy. On Friday, March 13th, just like everybody else in the industry, we were paying attention to the cancellations.” They canceled that night’s show, he adds, “But our production manager Jeff Hatfield said, ‘We don’t know what’s happening tomorrow. You’ll get a call in the morning. Sure enough, Saturday, 9 am, my phone rang, but walking into the dark building – it was pretty eerie.” Moving forward, the show continued with a skeleton crew and no audience, going out live on SiriusXM Satellite Radio, WSM Radio, Circle TV, and Circle On Demand.

The partnership with Circle TV started in January 2020, explains front of house engineer Kevin McGinty: “Initially it wasn’t live. They’d take cuts from the week, assemble them and post the show. During the pandemic, it became a live weekly television show, with blocking, sound checks – stuff we never had before – so we’d get to hear an artist beforehand and know what’s coming.”

The pre-pandemic shows sound like a “throw and go” but the depth of knowledge, and the lengthy experience the production staff has in the venue, with the rig, and handling lightning-fast changeovers and multiple artists, mean any hiccups are few, far between, and minor.

“It’s a huge team effort every night we go live,” Bussiere says, citing the work of Williams, McGinty, Nic Faddy (A-2 stage audio/backline manager), audio service supervisor Mark Thomas (who pitched Bussiere on moving from Clair Brothers to the Opry in 2016), and Jeff Ent, who maintains the Opry’s infrastructure/network/updates and doesn’t have an official title, with Bussiere referring to him as “our resident genius.”

“They know all of our systems inside, outside, and upside down,” Williams adds. “Jeff and Nic can drive in any of our positions – which I can’t do. They’re crucial, and because of how we communicate with each other, the way they run the deck and get information to us, nobody sees anything but a well-oiled machine.”

Fueling The Machine

Beyond teamwork and skill, it’s information and communication that fuel that machine. To facilitate that they have a simple but effective system implemented by McGinty when he started at the Opry 18 years ago: a FileMaker Pro database detailing the setup of every incoming artist. Constantly updated on a show-by-show basis, it contains all the information from past appearances and enables the engineers to make any necessary changes on the fly.

“I started that so I could keep everything straight in my head,” McGinty explains, “because it was absolute chaos every night. The stagehands knew what to do, but I was like, ‘What’s going on?’ So I started the FileMaker thing and it’s evolved until it became the way we keep everything together. There’s not a lot of time for communication when you’ve got 90 seconds between acts. You need to see what’s coming up without a whole lot of radio chatter. So, that gets updated, we know what’s coming up and can build our show in advance and see who they’re bringing in and work accordingly. It’s become our input list/stage plot Bible.”

From a single laptop, that’s evolved into a system anyone can view and update via multiple iPads on stage. “So, say someone says, ‘Hey, we’re not gonna plug anything in, we’ll just gather around one mic tonight,’ we make that update and everybody – front of house, broadcast, stagehands – can access it,” says Bussiere. “It’s slick. I always fire it up first thing and transfer all the info into FileMaker for that show and, when I make our show list, go through each act, get an update or generalization of what’s happening with them – like what musicians they’re bringing in – and then everyone’s got it.”

There’s still real-time communications, Williams notes: “If something’s changed with a returning performer, the stagehands put a flare up. We’re super house proud. We take it personally when something goes wrong, so mistakes are very small and very rare. When people come for the first time they say, ‘This was unlike anything I’ve ever done – it’s unbelievably smooth.’ It’s so slick and greased artists hardly know they’ve been on and off the deck. They’re like, ‘Did we just play a show?’ and we say, ‘Yes, you did, and it was great.’”

“As time goes on, it just grows and grows,” McGinty adds. “And there’s entries in there from when we started it, so you can look and go, ‘there’s Merle Haggard‘s input list, there’s Porter Wagoner’s…”

The engineers also archive past performances on their respective consoles. Bussiere explains how monitor world’s archive has grown over time: “In February 2017, when we started our season, I had a new (Yamaha) PM10 Rivage desk with four snapshots – All Mute, Start Here, Duet, and Opry Band. When we finished the season in October we had about 280 different scenes. Currently, I think it’s at 500.”

Since McGinty moved from being a “floater engineer” to FOH roughly six years ago, he’s accumulated some 400 snapshots on his Studer Vista 5 M2 console. “Because we don’t sound check or rehearse unless there’s television involved, you might have a show with an artist you haven’t seen in three years and already have their snapshot in there,” he notes. And if a change does come up and hasn’t been flagged yet, he adds, “Well, the longer you do this the more it’s like ‘this just looks wrong,’ so you adjust it or, if a snapshot’s looks kind of crazy, I’m not opposed to just starting over.”

Keeping the stage layout as consistent as possible is also helpful. “The Opry band has two electric guitar players, an acoustic/utility player, keyboards, bass, steel, drums, and background singers,” Bussiere says. “To reduce the amount of people backstage and on stage during Covid artists just performed with the Opry band backing them. We didn’t allow them to bring in their bands, but when things started loosening up a bit we’d allow one guest musician.

“So, downstage right we’ve got ‘Mix 1’ – so there’s ‘Amp 1’ for guest electric guitarists, a vocal mic we refer to ‘Sing 1’, and then ‘DI 1’, and an instrument mic, ‘Instrument 1. We do that for each of the five downstage mixes. Downstage left we have our electric amplifier 2, so there’s two downstage electric guitar amps for guest musicians. Then two positions we refer to as ‘Amp 3 and 4’. They’re behind the artist, downstage of our drums, for folks bringing a guitar amplifier like Keith Urban or Brad Paisley.”

Key Criteria

When it comes to audio gear, Bussiere states that reliability and rider friendliness are key across the board. “We generally use (Shure) SM58s for all of our vocals, and all Radial DIs, which are great but we still go through them.”

It’s a similar ethic at FOH, McGinty notes, citing a shortlist of the MVP gear: “I have a Soundcraft Realtime Rack with 16 channels of Universal Audio I rely on pretty heavily mostly for the multiband stuff since this Studer doesn’t have a multiband. I’ve also got an analog Neve 5045 primary source enhancer. As far as audio processing, that’s about it. I also have a Mac Pro out I multi-track on.”

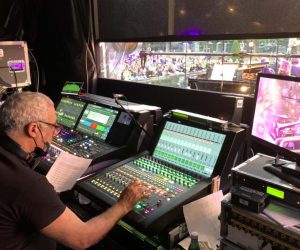

Since Williams started at the Opry in 2004, the technology and his workflow have evolved as well. “I’d been a recording engineer for a long while when they brought me on to mix broadcast, but I’ve always served more than one master here,” he says, laughing; explaining that he also does post-production, mixes for content for the marketing department and the Opry’s YouTube channel.

The Euphonix S5 he had previously was one of his favorite desks for mixing post. “The sonics are superb, but with the vast amount of snapshots we require, all the parameters I’m taking, and the enormous files I’m building, well, the Euphonix wasn’t really intended for that,” he explains, and it’s been replaced with a Studer Vista 9. “With the Core upgrades it’s essentially an X,” he adds. “As an on-air console, it’s extremely reliable and takes as many snapshots as I need to throw at it.”

Like McGinty and Bussiere, he has hundreds of them for returning artists. “And if artists show up on the regular, I keep refining the mixes, so I can start in a good spot as opposed to doing triage.

“Once the two-track leaves this room though, you can’t guarantee any of the other steps are going to work properly,” he continues. “One time, people listening were getting just the left side split into right and left. So I was asked to mix closer to mono – but I said no, because that may just cause another problem.” Now, however, he has more control. “So, the television and live streams sound very much like what I expect them to – to an unprecedented level.”

When Williams talks about his workflow, the information he’s taking in from everyone on the fly while mixing, the multiple broadcast channels his mix is going out to live, and the efforts he takes to limit the possibility of anything going south after the mix leaves his hands and heads out into the world, his gig sounds terrifying. He chuckles, saying:“I’ve had to learn to listen selectively given all the different guidance coming at me during a live television/radio broadcast, including the information from the deck for the Opry/radio side, and the direction and chatter from the TV PL set in the booth, simultaneously.”

All that said, he adds: “The brain’s an amazingly plastic thing and I’ve gotten used to it, but it was extraordinarily distracting at first.”

Back To The Future

Overall, it’s a far cry from the early days, Bussiere puts in, relating a conversation he had with long-time Opry member, Whispering Bill Anderson, who performed at the March 14, 2020 Saturday Night show. “I asked Bill, ‘What was it like playing the Ryman (Auditorium, former home of the Opry) back in the 60s?’ And he said: ‘You’d walk up to one microphone and mix yourself. If you wanted to be subtle you got further back from the mic.’”

In archived recordings from that time, Bussiere notes, “The audience sound played more of a role than it does now. If Minnie Pearl told a joke you could hear the laughter like you were sitting in there with them. Bill also said that he’d have to adjust what songs he’d play on the show because he knew a lot of times the audience wouldn’t hear what he was doing if a song had a lot of subtleties in it, or if it required a lot of attention, they might get distracted so he’d be like, ‘Yeah, I can’t do that one.’”

As changes go, the most recent are the most welcome. “We’ve returned to the normal state of busy at the Opry,” Williams says, “which is ‘rather,’” he adds, laughing. While at the time of our interview earlier this summer, they weren’t mounting the number of shows they had been pre-pandemic, they’re getting there. “We were at zero capacity, then 250, then 500 people, and in May we went to full capacity.”

It’s very much been a year of struggle and adjustment, Bussiere says. “It’s been pretty intense. Nobody knew what the hell was going on. We thought this would last three months, then six months… It was stressful just making sure everyone was safe. I referred to microphones for a while there as ‘germ bombs,’ but the Opry put a lot of thought into their protocols.”

Things are now significantly better, McGinty notes: “It’s more compelling to watch a lesser show with 50 people in attendance than the greatest band in the world with no audience. When we had the first audience last October last year after going six or seven months without one, it was dramatic. My heart was beating fast. One of the reasons you mix live sound is to get some sort of emotional feedback, and (without an audience) you’re not getting it.”

Now, though, it’s full-on again, he continues. “Not much changed in my workflow (during the pandemic), except I was mixing quieter. I mean, when you’re in an empty hall you’re like ‘85 dB is plenty.’ The room gets a little crazy as you approach triple digits, like when it gets loud in here for Reba or someone like that, so now it’s like, oh yeah, I remember this. And the artists come out here and they may have sat at home for a year and now they’re faced with 4,400 screaming fans, so it does get emotional.”

Great Moments

Although it’s been a tough time over the past year and a half, there are moments Bussiere recalls fondly, such as the second “Covid show” that featured just three artists – Marty Stuart, Vince Gill, and Brad Paisley. “There were some really special musical moments and that night was one of the best,” he says. “Marty’s a walking museum. So, when he brings an instrument in, I’ll always ask, ‘What’s the story behind that one?’”

That night, Stuart brought in Jimmy Rodgers’ first guitar. “The guys Jimmy worked with on the railroad bought it for him because he didn’t have a guitar at the time. So Vince walks out on stage and Marty tells Vince about the guitar and Vince immediately sat down and started playing it. There’s six or eight of us standing there listening. He probably played it for about five minutes, then looked at Marty and said, ‘Thank you. You don’t know how bad I needed that.’”

To document some of those moments, the Opry released a limited-edition vinyl LP titled Unbroken – Empty Room, Full Circle, featuring performances recorded during a time when Saturday Night Opry was the only game in town. It’s the brainchild of Opry general manager Dan Rogers, who acted as executive producer on the record.

“It’s curated cuts from the past year with no audience,” Williams says. “I have an Ampex ATR 102 at my studio so I brought it in to print the mixes to keep them as analog as possible as early up the chain as possible.” The result is an accurate, analog document of what they did in the room, he adds: “It’s a transcription of that.”

As Rogers puts it: “The performances featured on this album brought people together at a time in which they were otherwise largely separated. As a collection, they to me represent some of the most remarkable music made during what I believe will be looked on as a most pivotal time in Opry history.”